INTRODUCTION

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic T-cell mediated autoimmune disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical presentation and severity of disease. It may be localised to one site, e.g. scalp, nails, oral mucosa, or, it may become a more widespread mucocutaneous inflammatory condition affecting multiple sites, including the skin, oral cavity, anogenital skin, external ear, conjunctiva, lachrymal ducts, and oesophagus. Importantly it can result in significant scarring and stricture formation. The incidence of this more severe form varies between 0.22% and 1% of the adult population worldwide [1]. In contrast, oral lichen planus (OLP) seems to be more frequent with a reported incidence between 0.5% and 2.2% of the population being rare in children but presenting more usually in adults during their fourth to sixth decades with a female predominance of 2:1 [1]. The commonest oral lesions are reticular striae, but several clinical subtypes are recognised. Oral lesions may be long-lasting with a potential lifetime risk for malignant transformation in approximately 1% patients [3]. Dermatologists and other clinicians examining these patients must be aware of this risk and refer promptly when lesions are failing to resolve with treatment or are atypical.

AETIOPATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of LP is not yet fully understood but many factors have been implicated including genetic association, immune dysregulation, infections, drugs and contact factors among others.

Genetics

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region on chromosome 6 has been implicated in many autoimmune disorders.

In a phenome-wide association study 2(PheWAS) of 7481 subjects from the Marshfield Clinic Personalised Medicine Research Project in Wisconsin, USA where disease phenotypes (defined by their ICD9 codes) were mapped to this region, LP was the most significant phenotype association [4]. Haplotype HLA DBQ1*05:01 had the strongest link with LP. The study further demonstrated an association between a single peptide nucleotide (SNP) rs1794275 together with 5 other SNPs across the MHC. These are also associated with multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes. In a similarly well defined sub-group of scarring LP, the vulvovaginal gingival syndrome LP (VVG-LP), a strong association was reported with the DQB1*0201 allele. The authors have shown 28/35 (80%) patients having the DQB1*0201 allele versus 74/177 (41.8%) of healthy control subjects [5]. No other subgroups of LP were associated with this allele.

Other possible associations

Hepatitis C: There is evidence in the literature to suggest that in some geographic regions, OLP is associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. The association is stronger in Japanese and Mediteranean populations where the prevalence of hepatitis C is greater. The association may be related to their predisposition to other extrahepatic complications of HCV infection such as cryoglobulinaemia. Northern European patients are rarely associated with HCV [6].

Drugs: A wide range of drugs have been linked with lichenoid rashes. These include antimicrobials, antihypertensives, antimalarials, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, diuretics, metals, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and more recently intravenous immunoglobulins [2].

Anxiety/depression/stress: Patients with LP, in particular erosive LP have a higher reported incidence of anxiety and depression. Although exacerbations of OLP may be associated with episodes of anxiety and stress, a cause-and-effect relationship has not been identified [6].

Autoimmunity: There is an increased frequency of other autoimmune diseases in patients with OLP. A Taiwanese study of 12,427 LP patients and 49,708 age- and gender-matched controls drawn from a National database reported significant associations among LP patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, dermatomyositis, vitiligo and alopecia areata [7]. In a Swedish study, data from 956 patients with OLP and 1029 controls were collected using a standardized registration method. Patients with OLP used thyroid preparations (p <0.001) and NSAIDs (p <0.01) in higher proportions compared to controls. A multivariate logistic regression model demonstrated that levothyroxine was associated with OLP and by implication hypothyroidism [8]. In a subgroup of VVG-LP patients, 12/40 (30%) had another autoimmune disease with thyroid disorders present in six [5].

Immune dysregulation: LP is a T-cell mediated autoimmune disease. Histologically, it is characterised by a dense band of lymphocytes just below the epithelial basement membrane zone associated with saw-toothed rete ridges and apoptotic keratinocytes. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows a ragged fibrin band (Figure 1.1).

Evidence from chronic graft versus host disease suggests that lymphocytes are targeting antigens on keratinocytes that they recognise as foreign giving rise to lesions indistinguishable clinically and histologically from OLP [9]. Antigens may include altered self or extrinsic antigens (e.g. food, drugs, bacteria, viruses, dental materials).3

Figure 1.1: (a) Low-power view showing a sub-epithelial lymphocytic infiltrate that is well demarcated laterally. There is a mild degree of basal cell loss and some reactive rete hyperplasia focally. (Courtesy of Edward Odell, Oral Pathology, King's College London, London). (b) At higher power lymphocytes are seen associated with apoptosis in the basal and supra basal layers with basement membrane thickening, basal squamoid change and melanin dropout (Courtesy of Edward Odell, Oral Pathology, King's College London, London). (c) Ragged fibrin band characteristically seen in lichen planus with absence of a homogenous band of immunoglobulins or complement (Courtesy of Balbir Bhogal, St John's Institute of Dermatology, King's College London, London).

Figure 1.2: Potential pathogenic mechanisms for OLP. 1. Langerhans cells take up antigen and are induced by TNF and/or local inflammatory mediators to migrate to the local lymph node (LN). 2. From the local LN, CD4+ T cells preferentially move to the oral mucosa. 3. TNF-α, IF-γ and other cytoines induce E-selectin and MADcam-1 on surface of blood vessels. This leads to the selective recruitment of activated skin homing (CLA+) and gut α4β7 homing lymphocytes from the circulation. VCAM-1 is induced and ICAM-1 is increased on local blood vessels, necessary for lymphocytes to move across the vessel wall. 4. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells stimulated. 5. Chemokines including RANTES and MCP-1 attract a band of cytotoxic T cells which react with MHC class I on basal keratinocyte. TNF-α and IF-γ also induce ICAM-1 to be expressed on keratinocytes thus facilitating the migration of CD8+ lymphocytes into the epithelium. 6. Basal keratinocyte undergoes apoptosis.

The inflammatory cells believed to be involved in the process include T helper (CD4+) and T cytotoxic (CD8+) lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells. The proposed sequence of events is shown in Figure 1.2 whereby self-peptides are expressed and upregulated on the surface of keratinocytes. Langerhans's cells are recruited ultimately leading to clonal expansion of cytotoxic T cells with the help of T helper (CD4+) cells and IL12. Infiltration of cytotoxic T-cells in the epithelium leads to apoptosis of the basal keratinocytes. Possible mechanisms for apoptosis of keratinocytes include (1) TNF-α secreted by T cells binding to the TNF-α1 receptor on keratinocytes, (2) expression of CD95L (Fas ligand) on the surface of T cells, binding to CD95 (Fas) on the surface of keratinocytes and (3) cytotoxic T cells or NK cells releasing perforin which makes holes in the keratinocyte cell membrane and through which granzyme B secreted by T cells leads to cell death [10]. In addition, pro-inflammatory chemokines such as RANTES are produced by T lymphocytes, keratinocytes and mast cells among other cells. Several cell surface receptors for RANTES, e.g. CCR1, CCR3 CCR4 CCR5, CCR9, CCR10 have been identified in OLP. RANTES can attract mast cells which then degranulate and release TNF-α and more chemokines, further stimulating RANTES. This cycle has been implicated in disease chronicity. In susceptible individuals chronic presentation of antigen may perpetuate the condition [11].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF OLP

Idiopathic OLP is a symmetrical condition in contrast to an irritant or contact lichenoid reaction which is often asymmetrical. While patients typically present with a variety of clinical features, distinct patterns are recognised and the terminology can be helpful to describe features in individual cases (Table 1.1) [12,13]. Lichen planus results in a dysregulation of keratinocyte turnover so that areas may be thickened, thinned or ulcerated.5

|

Thus clinical subtypes include reticular, papular, plaque, atrophic, bullous and ulcerative subtypes (see Figure 1.3). The atrophic, bullous and ulcerative forms may lead to significant morbidity with discomfort during eating, swallowing or speech. The most commonly affected sites are the buccal mucosa, tongue and gingivae. The severity of OLP is broad ranging from mild and asymptomatic to severe, chronic, painful and ultimately leading to potential scarring. Approximately, 15% of patients with OLP go on to develop cutaneous lesions within several months of the initial onset of oral lesions.

Reticular OLP

The reticular form is the most common oral presentation frequently involving the buccal mucosa, lips, tongue or gingivae. While the majority of the patients are asymptomatic some may complain of roughness or dryness of the affected areas [14]. It presents as a white, linear or lacy pattern known as Wickham's striae. Within the reticular lesions, erythematous (atrophic) and ulcerative areas may develop (Figure 1.3).

Atrophic and ulcerative OLP

Atrophic lesions are common (44%) appearing as symptomatic erythematous areas and patients often report intolerance to spicy or acidic foods. When affecting the dorsum of the tongue, the lateral margins are affected initially leading to a hemilunar depapillation often with sparing of the lingual tip. Once lost the papillae do not reappear leaving a smooth atrophic surface. Within atrophic areas, progressive inflammation may lead to ulceration. Disease activity will fluctuate and most frequently affects the buccal mucosa, ventrolateral aspects of the tongue, gingivae and occasionally the lips. It is these patients that tend to present to dermatology clinics and where topical treatments fail to control symptoms, systemic therapy may be needed (see management algorithm).

Desquamative gingivitis

Gingival LP may be mild and appear as a glassy erythema with or without lichenoid striae or may progress to form areas of desquamation or frank ulceration known as desquamative gingivitis (DG) (see Figure 1.3c). Patients with DG may also be at risk of developing the VVG-LP sub-type or rarely in males peno-gingival LP. As seen in Figures 1.4a and b gingival LP may progress to a keratotic appearance and ultimately to verrucous changes that must be biopsied. These patients need to be monitored as they have a higher risk of developing dysplastic changes or an oral squamous cell carcinoma.6

Figure 1.3: (a) Reticular striae present in the buccal sulcus and gingivae. Some background atrophic changes represented as erythema. (b) Papular lesions evolving into plaque type LP on the dorsum of the tongue. Papillae have been lost over most of the surface with central sparing. (c) Desquamative gingivitis with frank ulceration around upper incisors.

Papular and plaque OLP

Papular LP is typically seen on the dorsal aspect of the tongue or buccal mucosa as slightly elevated areas which may eventually become more homogeneous (Fig 1.3b) [15]. Plaque type lesions may present on any oral mucosal site. Most frequently they arise on the buccal mucosa or dorsum of tongue. Generally, a biopsy is advisable as the lesions are frequently asymmetrical and may represent an area of dysplasia arising within OLP. In some patients plaques may become progressively thickened with a verrucous appearance as seen in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: (a) Desquamative gingivitis with subtle keratotic changes on the gingiva. (b) 4 years later developing into verruccous hyperplasia.

Bullous OLP

Bullous OLP is rare. Patients will report a history of blisters but clinically the appearance is of typical OLP. The history may suggest an overlap with mucous membrane pemphigoid 8and a biopsy for histology and immunofluorescence is required for diagnosis. A ragged basement membrane zone fibrin band (Figure 1.1c) and absence of linear immunoglobulins or C3 is consistent with LP [2].

CLINICAL VARIANTS OF PREDOMINANTLY MUCOSAL LP

Oro-genital involvement

It is not unusual for patients to have other mucosal sites affected or to present with an oro-genital type of LP. In females the percentage with vulval LP is unknown but in a small series of 37 cases was 51% and may be associated with considerable morbidity [16]. Perianal involvement extending to the natal cleft may be present. In males, the penis similarly may be affected often with classical lichenoid papules or an erosive balanitis in approximately 5%.

The vulvovaginal gingival subtype of lichen planus

The VVG-LP is an uncommon and severe variant of LP characterised by erosions or desquamation of the vulval, vaginal and gingival mucosae which may heal with scarring. Patients may develop complications such as loss of vulval architecture, vaginal synechiae or stenosis [5]. Desquamative or ulcerative gingivitis is the most prominent oral manifestation and is essential for the diagnosis unless patients are edentulous, having lost their teeth due to severe gingival LP or being misdiagnosed as having chronic periodontitis. Extragingival sites may additionally be affected and intraoral scarring may be a prominent feature. Vertical fibrous bands occur in the buccal mucosae and result in a reduced oral aperture as well as loss of the buccal sulcal depth. This may lead to the appearance of the buccal mucosa being attached to the neck of the lower molars and functionally compromises tooth-brushing and oral hygiene. Patients frequently have other sites affected in this syndrome as demonstrated in Figure 1.5. Scarring in these sites is often prominent, e.g. oesophageal strictures, urethral strictures, lacrimal duct stenosis, scarring of the external ear canal, scarring alopecia and nail involvement.

Figure 1.5: Sites of involvement in 40 patients with VVG-LP [5]. With permission from Journal of American Academy of Dermatology.

Therefore early recognition of VVG-LP and appropriate therapeutic 9measures may help to reduce the significant physical and psychological morbidity associated with this scarring type of LP. In males there is a variant called peno-gingival LP. This is generally less severe than VVG as the penile lesions are very responsive to topical treatments and are generally recognised and treated at an earlier stage.

Extraoral mucosal sites may also be affected in OLP patients not fulfilling the criteria for VVG-LP. All of these cases require a multi-disciplinary approach to management. The association with ocular involvement is now well described but is still under-recognised. The most commonly affected site is the eyelid, which is the location of the lacrimal duct through which tears drains into the nose. Lacrimal canalicular obstruction results in epiphora secondary to overproduction of tears or inadequate drainage. Complications include conjunctival infections from stagnant tears and eczematous changes on the lower eyelid due to frequent tearing. Ocular LP may occasionally result in conjunctival inflammation and subepithelial fibrosis [17]. Other mucosal sites include the nose with symptoms of nasal crusting and erosions, and the oesophagus with patients having dysphagia. Oesophageal involvement may respond to immunosuppressive agents but often requires repeated oesophageal dilatations or stenting depending on the severity of the stricture formation.

Extraoral mucosal involvement

Cutaneous LP, present in 25% of OLP patients is typically a self-limiting condition and tends to resolve within 6–24 months though it can recur. Hypertrophic LP may be more persistent and may last for many years. Other persistent sites include the nails, scalp and external auditory canals, the latter being associated with scarring of the ear canal and may lead to conductive hearing loss.

Malignant potential in oral LP

Lichen planus is one of a group known as an oral potentially malignant disorder (OPMD). A systematic review of 16 studies determined a range of 0% to 3.5% for incidence [18]. While the data across studies is inconsistent with variations in diagnostic criteria, incomplete long-term follow up and lack of control populations an overall rate of malignancy is estimated to be 1.09%. There is a higher risk of transformation when lesions are present on the tongue, buccal mucosa or gingiva [18] and in patients with high risk behaviours such as smoking and excessive alcohol intake. In OLP, patients with an atypical clinical appearance particularly where the mucosa develops a firm or gritty texture, those with areas of ulceration that fail to respond to treatment and those with evolving plaque type LP particularly on the gingivae may warrant serial biopsies and close follow-up.

MANAGEMENT

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is confirmed following a detailed history including concurrent medication, other autoimmune diseases, a full clinical examination confirming symmetrical lesions and where indicated confirmatory histopathology and DIF.

There are important differential diagnoses to consider:

- Lichenoid reactions to dental materials are typically asymmetrical or unilateral LP-like lesion and are in direct contact with the relevant dental restoration. Reactions 10may be irritant or allergic and if required, patch testing may be undertaken though for a localised reaction removal of the restoration is usually recommended [19]

- Systemic medication may lead to oral or cutaneous lichenoid lesions and may be difficult to distinguish from idiopathic LP. The temporal association with a new medication may be helpful

- Discoid lupus erythematosus may lead to lichenoid lesions. They are relatively painless and may have a characteristic ‘brush border’

- In patients with isolated DG without characteristic striae, immunobullous disorders such as pemphigus vulgaris or mucous membrane pemphigoid must be considered and investigated with DIF

- Finally plaque type LP, if isolated needs careful investigation and histopathology to confirm LP and exclude dysplasia

Assessment

Following a confirmed diagnosis, patients are examined for disease activity and overall severity. It is important to document carefully that each oral site has been examined enabling a more objective assessment of response to treatment over time.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An oral disease 11severity score (ODSS) devised and validated by the Oral Medicine Department at Guy's and St Thomas’ Hospital in 2007 is one such method. (Table 1.2). Sequential scores will then help to inform management and the success or otherwise of interventions. Clinical photographs may also be helpful for monitoring suspicious areas as in Figure 1.4.

Site score

- 0 = no visible lesion;

- buccal mucosa 1 = <50% of affected and 2 = >50%;

- dorsum of tongue, floor of mouth, hard or soft palate or oropharynx: 1 = unilateral lesion 2 = bilateral lesions

Activity score

0 | asymptomatic white lesions |

1 | mild erythema (glassy erythema or erythema localised to 3 mm along margins of teeth) |

2 | Marked erythema (full thickness gingivitis, extensive atrophy or oedema on non-keratinised mucosa) |

3 | Ulceration at this site |

Pain score

Analogue scale from 0 (no discomfort) to 10 (the most severe pain they have encountered with this condition so far). The patient is asked to provide a score reflecting their pain/discomfort as an average during the preceding week.

General measures

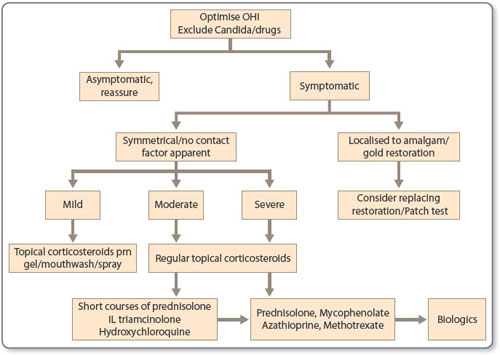

Maintenance of a high standard of oral hygiene is paramount as accumulation of plaque aggravates mucosal inflammation. Antiseptic mouthwashes such as 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate (Corsodyl mouthwash or spray) twice weekly or 1.5% hydrogen peroxide 10 mL daily (e.g. Peroxyl TM mouthwash Colgate-Palmolive) may be helpful. It is also important to recognise and treat candida as this can further exacerbate symptoms in OLP. Recognition of possible irritant or contact allergic reactions such as from amalgam fillings may necessitate dental treatment and/or patch testing [2]. Once an assessment has been made as to the need or otherwise for treatment, a sequence of interventions may be considered (see Figure 1.6). Asymptomatic OLP requires no treatment and if the pattern is typical, patients may be reassured and discharged to their general dental practitioner for follow-up.

TOPICAL THERAPY

In symptomatic patients anti-inflammatory oral rinses or sprays containing benzydamine hydrochloride (e.g. Difflam 3M) or lignocaine gel may be used for analgesia. In 2011 a Cochrane review of OLP found no randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs) that compared topical corticosteroids with placebo in patients with symptomatic OLP. Thus, the authors concluded that there was no evidence that one steroid is any more effective than another [21]. In a later Cochrane review (2012) of erosive LP, there was weak evidence that 0.025% clobetasol propionate lipid-loaded microspheres significantly reduce pain compared to conventional ointment in a study of 50 participants [22].

In practice, topical corticosteroids are considered the mainstay of initial treatment and betamethasone sodium phosphate 0.5 mg in 10 mL water as a 3-minute rinse and spit preparation up to four times daily (UCB Pharma Ltd, Watford, UK) or fluticasone propionate nasules (400 µg nasules in 10 mL water) twice daily may be helpful.12

For localized lesions clobetasol – 17-propionate 0.05% mixed in equal amounts with Orabase (ConvaTec, Uxbridge, UK) applied directly to the sulci, labial or buccal mucosae or within close fitting special trays may be helpful. If used frequently and long term, monitoring for adrenal suppression is recommended. The Cochrane review found weak evidence that aloe vera may reduce the pain of OLP and improve the clinical signs of disease compared to placebo. There was weak and unreliable evidence that topical Ciclosporin solution reduced pain compared to 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide. While nonrandomised studies have shown efficacy with topical tacrolimus the Cochrane review found no evidence for reduced pain compared to either steroids or placebo. Furthermore long-term safety is still to be determined and therefore, this is used only in short courses. The authors have found this very helpful for atrophic or erosive lesions on the lips used up to twice daily for 6 weeks avoiding strong sunlight during treatment.

Second line treatment

There is no consensus for an approach to second-line therapy. Intralesional corticosteroid preparations (5–10 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide) once or twice weekly and repeated for 3–4 weeks may be used for localised ulceration. Thereafter the authors recommend a step-wise approach as detailed in Figure 1.6. Short courses of systemic steroids may be administered for rapid control of symptoms. Steroid-sparing agents, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate or ciclosporin, can be used with some evidence to support efficacy but there are no RCTs. Additionally systemic retinoids, antimalarials, 13dapsone, psoralen + UVA treatment (PUVA) and thalidomide have all been used with varied success. In our own clinical practice, favoured second approaches include short courses of prednisolone and/or hydroxychloroquine 200–400 mg daily. We would advocate consideration of this treatment in patients not yet requiring or not wishing to take immunosuppressive therapy [23]. Our data have shown improvement in ODSS scores in 18/43 (42%) patients by 3 months and 24/43 (56%) by 6 months. For recalcitrant oral lesions, or in severe cases of mucocutaneous LP, mycophenolate mofetil has been helpful when all other second line agents had failed [24].

Third line treatments

There is emerging evidence to suggest that biologics may be of benefit particularly when targeting TNF. In a recent literature review, Adalimumab successfully cleared a patient with oral and cutaneous LP in six weeks while in an OLP there was improvement with etanercept. While efalizumab and alefacept have also been associated with improvement they have both been withdrawn. Rituximab has been successful in one further patient with mucocutaneous LP [25]. Finally preliminary evidence is emerging to support the novel phosphodiesterase type IV inhibitor, apremilast in mucocutaneous LP.

FOLLOW-UP

Patients with symptomatic disease will require regular follow-up in secondary care, usually in an oral medicine department or in a combined oral dermatology setting. Patients on immunosuppressive agents will require 3-monthly blood tests and sequential disease severity scoring. The World Health Organisation has classified OLP as a premalignant condition. Therefore, patients with a diagnosis of OLP and either atypical or symptomatic disease should be informed of the low risk of cancer development and be monitored appropriately.

CONCLUSION

In summary the pathogenesis of mucosal LP is complex involving antigen presentation by oral keratinocytes leading to targeted inflammation and apoptosis of the basal epithelium. As these pathways are further elucidated, so more targeted therapies will emerge. In the meantime, it is important that clinicians recognise patients that require careful monitoring by a specialist MDT or oral medicine team. It is also important that they appreciate the scarring potential of mucosal LP particularly where patients have VVG-LP, ocular, oesophageal or otic disease, as early intervention may reduce the complication and associated morbidity.

REFERENCES

- Vincent P, Breathnach SM, Le Cleach L. Lichen Planus and Lichenoid Disorders. In: Griffiths C, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 4 Volume Set. Wiley, 2016.

- Setterfield JF, Black MM, Challacombe SJ. The management of oral lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:176–182.

- Greenberg MS. AAOM Clinical Practice Statement: Subject: Oral lichen planus and oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016;122:440–441.

- Liu J, Ye Z, Maher JG, et al. Phenome-wide association study maps new diseases to the human major histocompatibility complex region. J Med Genet 2016;53:681–689.

- Setterfield JF, Neill S, Shirlaw PJ, et al. The vulvovaginal gingival syndrome: A severe subgroup of lichen planus with characteristic clinical features and a novel association with the class II HLA DQB1*0201 allele. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;55:98–113.

- Kurago Z. Aetiology and pathogenesis of oral lichen planus: an overview, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016;122:72–80.

- Chung PI, Hwang CY, Chen YJ, et al. Autoimmune comorbid diseases associated with lichen planus: A nationwide case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:1570–1575.

- Robledo-Sierra J, Mattsson U, Jontell M. Use of systemic medication in patients with oral lichen planus-a possible association with hypothyroidism. Oral Dis 2013;19:313–319.

- Thornhill MH, Sankar V, Xu XJ, et al. The role of histopathological characteristics in distinguishing amalgam-associated oral lichenoid and oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med 2006;35:233–240.

- Thornhill MH. The current understanding of the aetiology of oral lichen planus. Oral Diseases 2010;16:507–508.

- Nogueira PA, Carneiro S, Ramos-e-Silva M. Oral lichen planus: an update on its pathogenesis Int Dermatol 2015;54:1005–1010.

- Andreasen JO. Oral lichen planus 1. A clinical evaluation of 115 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1968;25:31–42.

- Thom JJ, Holmstrup P, Rindum J, Pindborg JJ. Course of various clinical forms of oral lichen planus. A prospective follow-up study of 611 patients. J Oral Pathol 1988;17:213–218.

- Ion DI, Setterfield JF. Oral Lichen Planus. Prim Dent J 2016;5:40–44.

- Van Der Waal J. Oral Lichen planus. In: Slootweg P. Dental and oral pathology. Switzerland: Springer Reference 2016:290–293.

- Lewis FM, Shah M, Harrington CI. Vulval involvement in lichen planus: a study of 37 women. Br J Dermatol 1996;135:89.

- Webber NK, Setterfield JF, Lewis FM, et al. Lacrimal canalicular duct scarring in patients with lichen planus. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:224–227.

- Thornhill MH, Pemberton MW, Simmons RK, Theaker ED. Amalgam contact hypersensitivity lesions and oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path 2003;95:291–299.

- Escudier M, Ahmed A, Shirlaw PJ, et al. A scoring system for assessing Oral Mucosal Diseases: Application to oral lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:765–770.

- Thongprasom K, Carrozzo M, Furness S, Lodi G. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD001168.

- Cheng S, Kirtschig G, Cooper S, et al. Interventions for erosive lichen planus affecting mucosal sites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD008092.

- McParland H, Momen SE, Ormond M, et al. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in 43 patients with oral lichen planus (abstr). Oral Dis 2016;22:14.

- Wee JS, Shirlaw PJ, Challacombe SJ, Setterfield JF. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in severe mucocutaneous lichen planus: a retrospective review of 10 patients. Br J Dermatol 2012;167: 36–43.