The term pudendum or vulva includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule, vestibular bulb and the greater vestibular glands (Figs 1.1 and 1.2).

MONS PUBIS

This name refers to the rounded eminence situated anterior to the pubic symphysis, formed by a mass of subcutaneous adipose connective tissue, covered by coarse hair at the time of puberty over an area usually limited above by an approximately horizontal boundary.

LABIA MAJORA

These two prominent, longitudinal, cutaneous folds extending back from the mons pubis to the perineum form the lateral boundaries of the pudendal cleft, into which the vagina and urethra open. Each labium has an external, pigmented surface, covered with crisp hair and a pink, smooth, internal surface with large sebaceous follicles. Between these surfaces is a large amount of loose connective and adipose tissue, intermixed with smooth muscle resembling the scrotal dartos muscle, together with vessels, nerves and glands.

The uterine round ligament may end in the adipose tissue and skin in the anterior part of the labium. A persistent processus vaginalis and congenital inguinal hernia may also reach a labium. The labia are thicker in front, where they join to form the anterior commissure. Posteriorly they do not join but merge into neighbouring skin, ending near and almost parallel to each other; with the connecting skin between they form a low ridge, the posterior commissure, which overlies the perineal body; this is the posterior limit of the vulva; the interval between this and the anus, a distance of 2.5–3 cm, is the ‘gynecological’ perineum.

Labia Minora

These two small cutaneous folds, devoid of fat, between the labia majora, extend from the clitoris obliquely down, laterally and back for about 4 cm, flanking the vaginal orifice. In virgins their posterior ends may be joined by the cutaneous frenulum of the labia minora. Anteriorly, each labium minus bifurcates, its upper layer passing above the clitoris to form with its fellow a fold, the prepuce, overhanging the glans clitoridis. The lower layer passes below the clitoris to form with its fellow the frenulum clitoridis. Sebaceous follicles are numerous on the apposed labial surfaces. Sometimes an extra labial fold (labium tertium) is found on one or both sides between the labia minora and majora.

Vestibule

This cavity lies between the labia minora. It contains the vaginal and external urethral orifices and the openings of the two greater vestibular glands, and those of numerous mucous lesser vestibular glands. Between the vaginal orifice and the frenulum of the labia minora is a shallow vestibular fossa.

Clitoris

This is an erectile structure, homologous with the penis, and lies postero-inferior to the anterior commissure, partially enclosed by the anterior, bifurcated ends of the labia minora. The corpus clitoridis has two corpora cavernosa, composed of erectile tissue and enclosed in dense fibrous tissue separated medially by an incomplete fibrous pectiniform septum; each corpus cavernosum is connected to its ischiopubic ramus by a crus. The glans clitoridis is a small round tubercle of spongy erectile tissue; its epithelium has high cutaneous sensitivity, important in sexual responses. The clitoris, like the penis, has a ‘suspensory’ ligament and two small muscles, the ischiocavernosi attached to its crura. In many details it is a small version of the penis, but differs from it basically in being separate from the urethra.

VAGINAL ORIFICE (INTROITUS)

This is usually a sagittal slit positioned postero-inferior to the urethral meatus; its size varies inversely with that of the hymen; like the vagina it is capable of great distension during parturition and to a lesser degree during coitus.

Hymen Vaginae

This is a thin fold of mucous membrane situated just within the vaginal orifice; the internal surfaces of the fold are normally folded to contact each other and the vaginal orifice appears as a cleft between them. The hymen varies greatly in shape and area; when stretched, it is annular and widest posteriorly; sometimes it is semilunar, concave towards the pubes; occasionally it is cribriform or fringed. It may be absent or form a complete, imperforate hymen. When it is ruptured, small round carunculae hymenales are its remnants. It has no established function.

External Urethral Orifice

This opens about 2.5 cm postero-inferior to the glans clitoridis, anterior to the vaginal orifice: it is usually a short, sagittal cleft with slightly raised margins and is very distensible. It varies in shape from a round aperture to a slit, crescent or stellate form.

BULBS OF THE VESTIBULE

These are homologues of the single penile bulb and corpus spongiosum. They are two elongate erectile masses, flanking the vaginal orifice and united in front of it by a narrow commissura bulborum (pars intermedia). Each lateral mass is about 3 cm in length; their posterior ends are expanded and are in contact with the greater vestibular glands; their anterior ends are tapered and joined to one another by a commissure, and to the glans clitoridis by two slender bands of erectile tissue. Their deep surfaces contact the inferior aspect of the 5urogenital diaphragm. Superficially each is covered by a muscle, the bulbospongiosus. Thus, the female corpus spongiosum is cleft into bilateral masses, except in its most anterior region, by the vestibule and the vaginal and urethral orifices.

GREATER VESTIBULAR GLANDS [GLANDS OF BARTHOLIN]

These are homologues of the male bulbo-urethral glands; they consist of two small, round or oval reddish-yellow bodies, flanking the vaginal orifice, in contact with and often overlapped by the posterior end of the vestibular bulb. Each opens into the vestibule, by a duct of about 2 cm, in the groove between the hymen and labium minus. They are not infrequent sources of vulval neoplasm. In microstructure, the glands are composed of tubulo-acinar tissue, its secretary cells columnar in shape, secreting clear or whitish mucus with lubricant properties, stimulated by sexual arousal. In addition, recent studies have shown the presence of endocrine cells in these and the minor glands of the vestibule, using immunohistochemical methods; their contents include serotonin, calcitonin, bombesin, hCG and katacalcin.1

CHANGES IN VULVA WITH AGE AND PARITY

The tissues of vulva are sensitive to sex hormones mainly estrogen, so with age, changes do occur in vulva.

In newborn babies, labia majora are plump due to maternal hormones. As the effects of maternal hormones wean off, labia majora become thinner and labia minora and clitoris become relatively prominent and protruding.

In Adolescent stage, female hormones start increasing causing an increase in labial fat making labia minora and vaginal orifice get hidden between two labia majoras. Pubic hair starts developing on mons pubis and later on labia majora. Labia minora is devoid of hair follicles. With sexual activity hymen gets torn.

During pregnancy, vulva and vagina become hyperemic and engorged due to increased blood flow. This can greatly increase sexual sensitivity and pleasure. The increased amount of discharge can even cause considerable wetness and can also promote growth of pathological organisms. Candidal vulvitis is a common condition encountered during pregnancy. Increased blood supply can even lead to varicosities in vulva which may bleed profusely when ruptured during sexual contact or at the time of delivery.

During child birth, fourchette and perineum get torn and lax and heal by scarring.

Multiparity can lead to short perineal body, laxity, wear and tear of perineal muscles.

In old age, all the tissues get atrophied due to estrogen deficiency and skin become dry and thin. Labia minora may shrink and merge into surrounding tissues. Pubic hair becomes sparse. Perineal muscle tone decreases due to estrogen deficiency, making uterovaginal prolapse more evident in this age group.

Blood Supply [Fig. 1.3]

The arterial blood supply, venous and lymph drainage and nerve supply of the female external genitalia resemble those of homologous structures in males.

Vulva is supplied by internal pudendal artery and its branches. Internal pudendal artery is the terminal branch of the internal iliac artery which passes out of the pelvis through greater sciatic notch, curls around ischial spine and returns to the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa through lesser sciatic notch. It enters the layers of the triangular ligament to give branches to the labia, vagina, and bulbs of the vestibule, perineum and various muscles. It ends as the dorsal artery of the clitoris.

The veins of the vulva accompany the arteries and drain into internal pudendal vein, ultimately into internal iliac vein.

During vulvectomy, we have to keep in mind the surface anatomy of the nerves and vessels so as to avoid inadvertent damage and excessive blood loss. The main branches of the internal pudendal artery can be ligated beforehand.

Nerve Supply [Fig. 1.3]

The skin of the vulva is very sensitive and perineal injuries are especially painful.

Mons veneris and the foreparts of the vulva are supplied by the ilio-inguinal nerve and genital branch of genito femoral nerve both arising from L1 and L2 roots of the lumbar plexus. Clitoris is richly supplied by nerves and is highly sensitive. It gets erected during sexual excitation. The outer and posterior parts of the labia and the perineum receive some sensory fibres from the posterior cutaneous nerve of thigh.2

The pudendal nerve supplies sensory fibres to the skin of the vulva, external urethral meatus, clitoris, perineum and the lower vagina. It provides motor fibres to all the voluntary muscles, including the compressor uretherae, sphincter vaginae, levator ani and external anal sphincter.

Pudendal block (Fig. 1.4) is carried out by injecting a local anesthetic solution around the nerve as it circles the ischial spine and comes to lie on the medial aspect of the inferior pubic ramus. In order to obtain complete anesthesia of the vulva, the other cutaneous nerves require to be injected. Relaxation of the levator ani needs direct infiltration of the muscle and its fascial coats because the muscle is partly innervated from above by fibres arising directly from S3 and S4 roots.

CLINICAL APPLICATION

- Pudendal nerve block is given to relax the perineal muscles so as to facilitate intravaginal manipulations during child birth or any other procedure. As already described, pudendal nerve curls around the ischial spine along with internal pudendal vessels and comes to lie on the medial aspect of the inferior pubic ramus. Therefore, to avoid injury to accompanying vessels, local anesthetic solution is injected around the nerve, 2 cm medial to ischial spine in sacrospinous ligament

- As vulva is supplied by different nerves, pudendal nerve block alone cannot cause complete anesthesia of the vulva. Thus, it is necessary to supplement it with local infiltration of the vulval skin before giving episiotomy.

- For complete relaxation of the perineum, direct infiltration of the levator ani is also required because the muscle is partly innervated from above by fibres arising directly from S3 and S4 roots.

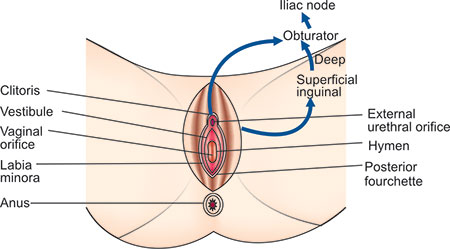

Lymphatic Drainage [Fig. 1.5]

Lymphatic drainage from the vulva is now known with accuracy. The labia majora and minora and clitoris drain primarily to the superficial and deep inguinal nodes then secondarily to the pelvic glands (Fig. 1.1).3, 4

Lymphatic drainage to vulva begins with minute papillae and these are connected in turn to a multilayered meshwork of fine vessels which is always limited to an area medial to genito crural fold.7

Fig. 1.5: Lymphatic drainage of carcinoma vulva (Note the possible contralateral spread of cancer especially from anterior vulva and clitoris)

Labia majora and minora drain primarily to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. There are 12–20 superficial inguinal lymph nodes and they lie in a T-shaped distribution 1 cm below the inguinal ligament, with the stem extending down along the saphenous vein. The nodes are divided into four quadrants with the centre of division at the saphenous opening. The vulvar drainage goes primarily to the medial nodes of upper division. These nodes lie deep in the adipose layer of the subcutaneous tissues, in the membranous layer, just superficial to the fascia lata. Lymphatics from superficial nodes enter the fossa ovalis and drain into deep inguinal nodes, which lie in the femoral canal of the femoral triangle. The fourchette drainage follows that of labia. The clitoris has alternate channels either over the symphysis pubis to the external iliac group of lymph nodes or to the obturator nodes via the dorsal vein of the clitoris. These direct entries to the pelvic system may account for the higher incidence of pelvic gland metastasis with clitoral lesions over those of labial lesions (Fig. 1.5).5,6

Confluence of this lymphatic network renders contra-lateral metastasis not unusual and even frequent in incidence.

Most authors agree that superficial inguinal glands can serve as the sentinel nodes of the vulva. The deep femoral nodes are the secondary node recipients and are involved before drainage into deep pelvic nodes occurs. Lymphatic drainage of the vulva is a progressive systemic mechanism and therapy can be planned according to where in the lymphatic chain tumor can be present.7, 8

Although lymphatic drainage from the clitoris directly into the deep pelvic nodes is described, their clinical significance seems to be minimal. It is unusual to find a case with metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes without metastasis to inguinal nodes, even when clitoris is involved.

The knowledge of the lymphatic drainage of the vulva is very crucial as spread of squamous cell cancer of the vulva is mainly by lymphatic route. Lymph glands are usually involved in succession as described above. It helps in staging the vulval malignancy and deciding its management.

During surgical management of carcinoma vulva, lymphatic drainage of the involved vulva is kept in mind. If the inguinal lymph nodes are not involved, pelvic lymphadenectomy is not generally required.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important to understand the detailed anatomy and lymphatic drainage and blood supply of vulva especially when operating for vulval malignancy. Vulva includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule, vestibular bulb and the greater vestibular glands. It is supplied by internal pudendal vessels and its branches. It is very richly innervated by pudendal nerve, ilio-inguinal nerve, genital branch of genitor-femoral nerve and posterior cutaneous nerve of thigh. Lymphatic of vulva drain primarily into superficial and deep inguinal group of lymph nodes then secondarily to the pelvic glands.8

REFERENCES

- Fetissof F, Arbeille B, Bellet D, Barre I, Lansac J. Endocrine cells in human Bartholin's glands. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Virchow's Archiv B-Cell Pathol Mol Biol 1989; 57: 117–21.

- Bhatla N. Anatomy. In: Neerja Bhatla ed. Jeffcoate's Principles of Gynaecology. 6th ed. Arnold Publishers, London, New Delhi: 2001; 56–7.

- Parry Jones. Lymphatics of the vulva. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1960; 67: 919.

- Way S. The anatomy of the lymphatic drainage of the vulva and its influence on the radical operation for carcinoma. Ann Coll Surg Eng 1948; 3: 187.

- Krupp PJ, Bohm JW. Lymph gland metastasis in invasive squamous cell cancer of the vulva. Am j Obstet Gynecol 1978; 130: 943.

- Rutledge F, Smith JP, Franklin EW. Carcinoma of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1970; 106: 1117.

- Mitchel S. Hoffman, Danis Cavanagh. Malignancies of the vulva. In: Rock JA, Thompson JD eds. Te Linde's Operative Gynaecology 8th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia: 1996; 1331–3.

- Krupp PJ. Invasive tumors of vulva: Clinical features and management. In: Coppleson M ed. Gynaecologic Oncology Fundamental Principles and Clinical Practice. Churchill Livingstone, London: 1981; 1: 331–3.