OVERVIEW

Over the past few years, new treatment techniques and diagnostic studies have been applied to vascular anomalies involving the airway. Vascular anomalies as defined by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies consist of any vessel type: artery, vein and lymphatic (Table 1).1 Airway vascular lesions are often detected in childhood when the airway diameter is small. These lesions are associated with specific signs and symptoms, related to impaired movement of air or food boluses. Most of the discussion in this chapter is applicable to pediatric airway vascular lesions.

2

DIAGNOSIS: CLINICAL

Most infantile hemangiomas occur in girls; whereas lymphatic and venous malformations occur equally in boys and girls.2,3 When encountering a patient with an airway vascular anomaly; a head and neck, and skin examination is essential to discover if the anomaly is limited to the airway.2,4 For example, airway infantile hemangioma can involve the facial skin or mucosal surfaces of the oropharynx or oral cavity in over 50% of cases (Zone 3) (Fig. 1).5,6 A similar number of patients with PHACES (Posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, coarctation of aorta, eye anomalies and sternal defects) syndrome can have airway infantile hema ngioma.4,7 A complete examination reveals clues as to the exact etiology of the airway vascular lesion, which is important for determining the most appropriate and effective treatment.

DIAGNOSIS: HISTOLOGIC

Anomalies of any type of vascular channel can involve the airway, which is frequently the laryngeal airway (Figs 2A to C. Most commonly these are primarily proliferative arterial lesions, known as infantile hemangioma.8 Infantile hemangioma can be distinguished histologically from other types of airway vascular lesions, such as venous or lymphatic.9 Infantile hemangiomas have a unique endothelial cell membrane receptor.10 This receptor is the glucose transporter isoform one (GLUT-1) (Flow chart 1). This is the same receptor that is detected in cutaneous or other infantile hemangioma. Lymphatic capillary endothelium can be distinguished from other types of endothelium by staining for podoplanin (D2-40).11

Figs 2A to C: Laryngeal vascular anomalies. (A) Infantile hemangioma; (B) Venous malformation; (C) Lymphatic malformation

Flow chart 1: Decision algorithm for assessment of airway vascular anomaly and potential need for tissue biopsy

AIRWAY ASSESSMENT

Airway vascular lesions can be diagnosed and characterized through imaging and endoscopy.9,12 Bedside endoscopy is sufficient for diagnosis of most airway lesions, but operative endoscopy is necessary to establish lesion extent and type. Computerized tomography angiograms (CTA) are excellent for high resolution depictions of high flow vascular lesions involving the airway, and head and neck region (Figs 3A and B).13,14 CTA angiography can also be obtained in a rapid sequence, so that airway imaging can be done without endotracheal intubation. Conversely, MRI scanning of the same area takes more time, necessitating endotracheal intubation and often does not allow resolution of small airway structures, such as the pediatric larynx.9 Assessment of upper and lower airway venous or lymphatic malformations remains challenging. The assessment is best done with a combination of awake and operative endoscopy, along with imaging studies. Operative endoscopy performed with suspension microlaryngoscopy and self-retaining laryngeal retractors offers excellent visualization of any airway vascular lesion (Fig. 4).155

Figs 3A and B: (A) Three-dimensional computerized tomography angiogram (CTA) of extensive Zone 3 or “beard distribution” infantile hemangioma in a patient with evidence for PHACE syndrome; (B) Two-dimensional sagittal CTA of the same patient demonstrating complete laryngeal involvement

Fig. 4: Self-retaining laryngeal retractors with endoscopic laryngeal visualization obtained with retraction of false vocal cords (upper left inset)

This increased field of view reduces vascular lesion trauma and often eliminates the need for bronchoscopy, since the airway is stabilized and tracheal visualization is improved.

TREATMENT

Airway infantile hemangiomas deserve special attention, as their treatment has changed radically in the last four years.16–18 The discovery that a nonselective beta blocker, propranolol (at a dose of 2mg/kg/day) 6shrinks some infantile hemangiomas, has been applied to airway infantile hemangioma treatment. This has reduced the need for surgical intervention.17 Early reports show successful airway infantile hemangiomas treatment with properly dosed propranolol, after diagnostic evaluations of the airway are complete. Long-term follow-up studies are not available. It seems that large, high stage, segmental hemangiomas, circumferentially involving the laryngeal airway; respond very well to propranolol (Figs 5A to C.2,8

Figs 5A to C: Endoscopic view of circumferential airway infantile hemangioma with transglottic involvement and extension into neck (Stage 3), treated solely with propranolol. Six weeks of age, 12 months of age and 30 months of age (A to C). Normal voice, swallow and no medication complications

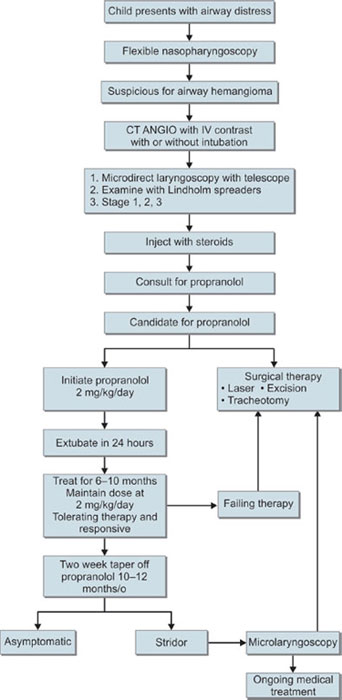

Prior to the treatment option of propranolol, these lesions were the most problematic. More localized, smaller stage, infantile meningiomas may not require propranolol therapy and could be potentially managed surgically, if so desired. While current treatment for infantile hemangiomas is evolving, the algorithm shown is a synthesis of multiple centers experience using propranolol as the primary treatment modality for airway infantile hemangioma (Flow chart 2).

In general, a localized endoluminal airway vascular lesion is often excisable in a single surgery using a variety of methods.19 This changes when the airway lesion extends from the airway into the surrounding structures. In this situation multimodal therapy with medication, sclerosis, and surgical excision may be necessary. Frequently staged interventions are required to possibly attain a stable safe airway.

The authors anticipate that in the coming years, more medical treatment options for airway vascular lesions will become available, reducing the need for surgical intervention and modifying treatment methodology while improving treatment efficacy and safety.8

REFERENCES

- North PE, Waner M, Buckmiller L, et al. Vascular tumors of infancy and childhood: beyond capillary hemangioma. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2006;15(6):303–17.

- Perkins JA, Duke W, Chen E, et al. Emerging concepts in airway infantile hemangioma assessment and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(2):207–12.

- Perkins JA, Manning SC, Tempero RM, et al. Lymphatic malformations: review of current treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(6):795-803,803 e1.

- Rudnick EF, Chen EY, Manning SC, et al. PHACES syndrome: otolaryngic considerations in recognition and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(2):281–8.

- Orlow SJ, Isakoff MS, Blei F. Increased risk of symptomatic hemangiomas of the airway in association with cutaneous hemangiomas in a “beard” distribution (see comments). J Pediatr. 1997;131(4):643–6.

- Waner M, North PE, Scherer KA, et al. The nonrandom distribution of facial hemangiomas. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):869–75.

- Haggstrom AN, Skillman S, Garzon MC, et al. Clinical spectrum and risk of PHACE syndrome in cutaneous and airway hemangiomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(7):680–7.

- O TM, Alexander RE, Lando T, et al. Segmental hemangiomas of the upper airway. Laryngoscope; 2009.

- Parhizkar N, Manning SC, Inglis AF, et al. How airway venous malformations differ from airway infantile hemangiomas. Arch OtolaryngolHead Neck; 2011.

- Badi AN, Kerschner JE, North PE, et al. Histopathologic and immunophenotypic profile of subglottic hemangioma: multicenter study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(9):1187–91.

- Perkins JA, Manning SC, Tempero RM, et al. Lymphatic malformations: current cellular and clinical investigations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(6):789–94.

- Perkins JA, Chen EY, Hoffer FA, et al. Proposal for staging airway hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(4):516–21.

- Bittles MA, Sidhu MK, Sze RW, et al. Multidetector CT angiography of pediatric vascular malformations and hemangiomas: utility of 3-D reformatting in differential diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(11):1100–6.

- Sidhu MK, Perkins JA, Shaw DW, et al. Ultrasound-guided endovenous diode laser in the treatment of congenital venous malformations: preliminary experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(6):879–84.

- Longstreet B, Bhama PK, Inglis AF, et al. Improved airway visualization during direct laryngoscopy using self-retaining laryngeal retractors: a quantitative study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(2):270–5.

- Truong MT, Perkins JA, Messner AH, et al. Propranolol for the treatment of airway hemangiomas: a case series and treatment algorithm. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(9):1043–8.

- Cushing SL, Boucek RJ, Manning SC, et al. Initial experience with a multidisciplinary strategy for initiation of propranolol therapy for infantile hemangiomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):78–84.

- Balakrishnan K, Perkins JA. Management of airway hemangiomas. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4(4):455–62.