REACHING A DIAGNOSIS

Is the Pain Functional or Organic?

The vast majority of patients who consult a doctor, especially in the primary care sector, with chronic abdominal pain, will have a functional rather than organic cause for the pain. Over-investigation of such patients is often counterproductive. Many of these investigations are unpleasant, even painful and associated with considerable cost and patients often get alarmed by the number of investigations and they tend to equate that to serious illness. It is therefore essential that the physician identifies those patients positively rather than negatively by excluding a whole lot of organic diseases.

Based on the UK general practitioner studies, the UK general practitioner with an average patient list will encounter over 25 new cases of functional bowel problems compared to a probability of 1 incidental case of colorectal cancer and the average general practitioner will encounter inflammatory bowel disease like a new case of Crohn's disease once every 7 years or more. Identifying the individuals who are likely to have an organic disease rather than a functional disease is therefore very important. Probably the single most important consideration is the patient's age. It is unsafe to label any chronic abdominal pain developing for the first time in a patient over 40 years of age as functional without further investigation. If the patient is under 40 years of age, then it is important to try to make a positive diagnosis of functional pain, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), from the history and ask specific questions if the answers are not provided spontaneously. These questions include:

- Is the pain associated with gaseous distention?

- Is the pain associated with constipation or diarrhea?

- Is the pain relieved by defecation?

A positive answer to the above questions usually suggests functional abdominal pain. Conversely, the pain is usually more likely to be organic and warrants further investigation regardless of the age if:

- It awakes the patient at night.

- It persists for weeks or many months.

- It is associated with persistent rather than intermittent alteration of bowel habit.

- It is accompanied by weight loss or rectal bleeding.

Thorough general examination including rectal examination and a few blood tests should usually suffice. A blood test should include full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or plasma viscosity and liver function tests (LFTs) as found in many automated serum profiles. Even if these are normal one can miss inflammatory bowel diseases, particularly Crohn's disease, especially if the patient comes from a high-prevalence country. Serum acute phase reactant test like C-reactive protein (CRP) can also be quite useful as it does reflect an inflammatory process. More recently, fecal calprotectin has been shown to be useful in differentiating between inflammatory bowel conditions and those with normal or IBS (Fig. 1.1). The prevalence of the conditions and incidental cases per year, per general practitioner, is given in Table 1.1.

A simple diagnostic algorithm to differentiate between IBS and other causes of abdominal pain is illustrated in Figure 1.2. When a physician encounters a patient with abdominal pain with some bowel symptoms, it is important to try to make a positive diagnosis of IBS early. This will reassure the patient, enable early implementation of treatments and prevent unnecessary and painful investigations.

Fig. 1.1: Fecal calprotectin IBS or IBD. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (CD: Crohn's disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; NC: Normal controls.)

Fig. 1.2: Diagnostic algorithm for IBS.

(IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-C: IBS-constipation; IBS-M: IBS-mixed; IBS-D: IBS-diarrhea; MRE: Magnetic resonance enteroclysis)

Symptoms that should concern the physician are:

- Age over 40 years

- A strong family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, any rectal bleeding

- Anemia

- Weight loss or

- Palpable abdominal mass.

If they do not have these symptoms, then the physician should proceed to obtain fecal calprotectin and, if that is negative, a firm diagnosis of IBS can be made. For the case of predominant diarrhea, refer to Chapter 3 for reaching a diagnosis.

Is it Due to Gastric or Duodenal Disease?

When pain is due to gastric or duodenal disease, it is usually in the epigastric region. Sometimes with posterior duodenal ulcers, the pain can radiate through to the back, but in general the pain is often poorly localized. A typical history would be of a patient being awakened at night with these symptoms and this is usually in the early hours of the morning. It is often periodic, it may last several weeks separated by weeks or months without pain.4

Patients taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may have duodenal ulcer disease with little or no symptoms at all, probably due to the analgesic effects of non-steroidal drugs themselves. As a result, they may present late and perhaps with a complication like bleeding or perforation. A history of drug use is important, therefore as part of the work-up for these patients.

The best way of diagnosing patients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) abdominal pain is to perform an endoscopy (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4). In patients under the age of 40 years, it is not unreasonable to carry out non-invasive investigations before considering an endoscopy. This could be a Helicobacter pylori fecal antigen test which is a simple and low-cost investigation. If the patient is young and presents with predominantly dyspeptic symptoms, it is also not unreasonable to give a trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) like lansoprazole or omeprazole to see if it alleviates the symptoms. However, in areas where there is a high incidence of gastric cancer, it is not unreasonable to perform a prompt endoscopy in order to detect early cases of gastric cancer.

Duodenal ulcer disease is associated with Helicobacter infection in the majority of patients without a history of non-steroidal use. The easiest and cheapest method of detecting H. pylori with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity is the fecal antigen test. However, other tests such as blood serum antigen testing and urea-based breath tests are also available.

Endoscopy remains the investigation of choice when there is a suspicion of gastroduodenal disease. A well performed endoscopy can be done without sedation or under light sedation and is usually very well tolerated. This would also be able to pick up suspicious pathology like early gastric cancer. If the endoscopist encounters an ulcer in the stomach, it would be mandatory to biopsy it and also to review it at an interval of 6–8 weeks after treatment to make sure it is healed completely.

5

Fig. 1.5: Duodenal adenoma: This is a benign lesion with malignant potential and can be removed endoscopically. Usually found around the papilla, this one in the first part of the duodenum is rare. May be associated with colonic polyposis syndromes hence colonoscopy should be offered.

This is to make absolutely sure that we are not dealing with gastric cancer. Ulcers in the first part of the duodenum are almost always benign, but malignant lesions can occur in the duodenum but tend to be in the second or third part of the duodenum or associated with the ampulla of Vater. A well-performed endoscopy should exclude all these possible lesions (Figs. 1.5 to 1.7).

A diagnosis of Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (gastrin-producing tumor) should be considered if there are extensive multiple duodenal ulcers or patients with ulcers resistant to treatment with PPIs, patients with extensive ulcers who are Helicobacter negative or continue to have ulcers after 6Helicobacter eradication. Investigations for Zollinger–Ellison syndrome include a fasting gastrin level. Sometimes calcium levels may also be elevated in MEN1 (Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1) syndrome. These patients have tumors in the 3 Ps—pituitary (e.g. prolactinoma), pancreas (gastrinoma), and parathyroid. The gastrinomas tend to be multiple. Imaging with computed tomography (CT) scanning is often sufficient to locate the lesions but other modalities like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be very useful. Transabdominal ultrasound may even be sufficient in some cases of locating a lesion. Pancreatic gastrinomas can also be localized using endoscopic ultrasonography, which has a higher sensitivity and specificity for pancreatic and duodenal gastrinomas.

Fig. 1.6: Biliary gastritis. Bile reflux into the stomach can be readily seen at endoscopy and the accompanying mucosal inflammation makes it an easy diagnosis.

Fig. 1.7: Retroflexing the scope reveals a raised lesion with altered blood. This is an adenocarcinoma.

Duodenitis

Duodenitis is usually an endoscopic or histological diagnosis rather than a clinical one. Many patients with duodenitis have little or no symptoms or symptoms that are indistinguishable from duodenal ulceration. Treatment is purely symptomatic.

Is it a Gallbladder Disease?

Gallstones are extremely common and are frequently completely asymptomatic. A common error is to attribute nebula symptoms of abdominal discomfort, bloating and fat intolerance to the gallstones. This may lead to unnecessary cholecystectomy. Patients would then still complain of the same functional symptoms despite the cholecystectomy. It is therefore important to make the firm diagnosis that the symptoms are attributable to the presence of gallstones.

Gallstones can cause two varieties of pain. This may be due to inflammation or it could be due to stones or tumor that is obstructing the outflow of the gallbladder. Forcible contractions against such an obstruction would result in pain. Pain also occurs if the gallstones are impacted infundibulum or the neck of the gallbladder or if they are extruded into the common bile duct and can obstruct the common bile duct.

A typical feature of biliary pain is epigastric or right upper quadrant pain that often radiates to the back or to the right shoulder blade associated with nausea or flatulence. These symptoms mimic the pain of IBS or peptic ulcer disease or even cardiac ischemia. If examinations carried out at a time when the patient has symptoms, tenderness in the right upper quadrant may be a useful sign.

The pain of biliary colic can be quite characteristic. It is often very memorable, very severe, and it rises to a crescendo and plateaus for about 30 minutes or so before diminishing again. Patients may have episodes of these pains and may be able to recall the episodes quite succinctly. These characteristic symptoms would point to a biliary cause for the patient's pain. If the patient just complains of a vague, generalized pain in the right upper quadrant this is usually not caused by biliary colic and removal of the gallbladder with or without stones usually is unproductive.

When stones dislodge into the common bile duct, then abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) may result with or without a rise in serum bilirubin; but when obstruction gets complete, then jaundice is inevitable. Sometimes stones impacted in the neck of the gallbladder can cause local edema, which can compress on the common bile duct and cause a degree of jaundice or abnormal LFTs. This is sometimes referred to as Mirizzi's syndrome.

Pain of an inflamed gallbladder is usually a constant right upper quadrant pain and can be exquisitely tender on palpation.8

Radiology

The best way of imaging a gallbladder is to perform an ultrasound scan. A well-performed ultrasound scan is usually very instructive. A well-fasted patient will have a distended gallbladder and gallstones usually cast an acoustic shadow giving characteristic pictures. The size of the common bile duct may also be measured and it should be no more than a few millimeters. Anything in excess of 6 mm usually suggests some ongoing pathology although the size of the duct will be dilated after cholecystectomy and becomes increasingly dilated with advancing age.

If other lesions are suspected, then a computed tomography (CT) scan would be a very useful investigation as it would likely image the pancreas rather better than an ultrasound scan. If stones in the common bile duct are suspected either from raised LFTs or if there is a dilated common bile duct without obvious stones, then it is reasonable to proceed to magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which is valuable in assessing the presence of common bile duct stones. The presence of common bile duct stones will require therapy with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) (Figs. 1.8 to 1.10).

Adenomyomatosis of the Gallbladder

Ultrasound scan can often pick up cholesterol accumulation in the gallbladder known as cholesterolosis and may also be associated with adenomyomatosis. This is a benign condition characterized by hyperplastic changes of the gallbladder wall, causing overgrowth of mucosa, thickening of muscle wall and formation of intramural diverticula or sinus track sometimes known as Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses. It may be seen on ultrasound scan as a tumor-like lesion but these are completely benign.

9

Fig. 1.9: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram (MRCP) showing three stones in the common bile duct as well as stones in the gallbladder.

Occasionally, ultrasound scan cannot differentiate between adenomyomatosis and gallbladder cancer and further imaging may be considered including MRI or CT scanning.

Gallstones

About 15% of the British adult population have gallstones. Hence, it is not uncommon to have patients presenting with right upper quadrant pain and found to have incidental gallstones, but the presence of gallstones does not necessarily mean that they are the cause of the patient's symptoms. If the patient has a definite acute cholecystitis, then there would be evidence on ultrasound scan of a thickening gallbladder. Then it is almost certain that the pain experienced would be related to the gallbladder and cholecystectomy would be the correct treatment option. Often patients present with more 10diffuse symptoms and therefore endoscopy is often required to make sure that there are no other upper GI causes of the pain and symptoms before considering cholecystectomy on the patient. Because the symptoms may not be related to the gallbladder and may really reflect underlying functional problems in many patients, as many as 40% still continue to have symptoms despite a cholecystectomy. Hence, it is important to get an accurate reliable history before proceeding to cholecystectomy. Additionally, it must be noted that the absence of a gallbladder carries with it its own problems. This is sometimes referred to as postcholecystectomy syndrome and includes biliary gastritis, reflux symptoms and diarrhea. Diarrhea is caused by unbuffered bile reaching the colon and irritating the colon.

Is it a Pancreatic Disease?

The pancreas is a difficult organ to investigate. It lies behind the duodenum and the stomach and therefore ultrasound scans can be unreliable because of overlying gas. Upper GI endoscopy only reveals gastric and duodenal mucosa and unlikely to pick up evidence of pancreatic disease. The vast majority of patients with epigastric pain will have functional bowel pain and not necessarily underlying pancreatic disease. A high index of suspicion of neoplastic disease is necessary if one is to avoid the common mistake of missing early and therefore treatable pancreatic lesions. Pain from the pancreas can be quite diverse. Pain arising from the head of the pancreas may cause a right upper quadrant type pain and sometimes radiating to the back. Lesions in the body are frequently epigastric and more likely to radiate to the back and lesions in the tail may present as left upper quadrant pain. Initially, pain may be provoked by meals, particularly meals high in fat content but gradually it will be more severe, constant and patients are often more comfortable sitting forward rather than lying on the back.

Biochemical Tests for Pancreatic Disease

Serological markers such as CA19-9 detect carbohydrate antigens expressed by mucus glycoproteins. When ducts of the pancreas are blocked, these mucus glycoproteins spill into the blood circulation and can be detected in very high levels in the blood. Hence, the very high levels of CA19-9 may indicate pancreatic tumor. However, the test is nonspecific and there are many other causes of elevated CA19-9. Any other mucus-secreting tumor or ascites may also cause a raised CA19-9. However, presence of raised CA19-9 would trigger the need for more radiological imaging of the pancreas.

Radiology

An ultrasound scan performed by a good operator in a non-gaseous abdomen can pick up pancreatic lesions. However, CT scans are more reliable. CT scans 11would show a pancreatic lesion and also help stage the lesion. Size of the lesion is perhaps less important than the invasion of the lesion into neighboring vascular structures like the superior mesenteric artery and portal vein, which would severely compromise the ability for the surgeon to do a curative resection.

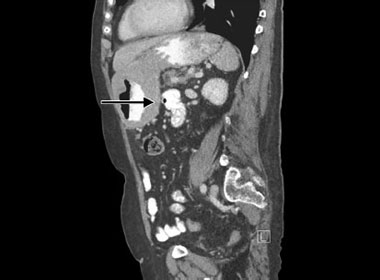

When the pancreatic lesion is in the head of the pancreas, the patient often presents with jaundice as a result of obstruction of the common bile duct. Once again a CT scan is helpful in staging the disease and making a diagnosis. An endoscopic ultrasound is also very helpful in further staging of disease, especially when it is in the head or the neck of the pancreas. Lesions in the tail of the pancreas are less accessible to endoscopic ultrasound (Figs. 1.11 to 1.17).

Fig. 1.11: Computed tomography of an inflamed swollen pancreas: This patient had azathioprine-induced pancreatitis.

Fig. 1.12: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas are potentially malignant intraductal epithelial neoplasms that are composed of mucin-producing columnar cells often present as incidental findings on scanning. The MRI shows a grossly dilated pancreatic duct.

Fig. 1.14: Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTC) showing dilated intrahepatic ducts and a tumor obstructing the lower end of common bile duct.

Is there an Intestinal Disease?

Pain arises from intestinal disease usually arises either from contractions of the intestine (colic) or due to distention of the bowel. Colicky-type abdominal pain can arise spontaneously as in IBS or as a result of an obstruction caused by a stricture. Because IBS is so common, in the absence of any “red flag” symptoms, it is wise to make a firm diagnosis of IBS rather than embark on expensive and sometimes unpleasant investigations. In patients without any of these alarming symptoms, a negative CRP, blood count and fecal calprotectin would exclude the majority of organic diseases and enables the physician to confidently make a diagnosis of IBS. A simple algorithm is found in Figure 1.2.13

Figs. 1.15A and B: Pancreatic tumor with dilated intrahepatic ducts. (A) Transverse and (B) Coronal images of tumor.

Fig. 1.17: Magnetic resonance imaging showing marked thickening of the terminal ileum with surrounding inflammation: This is typical of terminal ileal Crohn's disease.

Imaging

In a younger patient with symptoms of abdominal pain with weight loss, mild anemia or positive fecal calprotectin, always suspect inflammatory disease of the bowel like Crohn's disease. If there is associated rectal bleeding or diarrhea, it could suggest colonic involvement with inflammatory bowel disease, either ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease. In general, ulcerative colitis, being a mucosal disease, does not result in abdominal pain except when there is a complication like perforation or megacolon. Crohn's disease being a transmural disease can cause irritation of the parietal peritoneum and therefore pain is often a predominant feature.

In the older patient presenting with any of these symptoms, the principal condition to exclude is colonic neoplasia. Some form of imaging is therefore necessary in both groups of patients.

Colonoscopy is by far the best imaging modality as it would pick up any colonic neoplasia and the majority of patients with colonic or ileocolonic inflammatory bowel disease. A skillful colonoscopist should be able to enter the terminal ileum and assess the terminal ileum in over 90% of patients. Inflammatory changes in the colon are very common in patients with Crohn's disease, even in those with predominant ileal disease. If the patient is unable to have a colonoscopy for whatever reason, then the alternative is CT colography or MRI scanning. In patients where colon cancer is being suspected, particularly the older age group, CT colography can be a useful alternative to colonoscopy. It may be an alternative in individuals for whom colonoscopy is deemed too invasive, especially in the frail elderly patient. There are limitations to CT colography. Polypoidal lesions can be difficult to differentiate from particulate feces and it is clearly not possible to carry out biopsies and histological examination of any lesions seen. Often when 15a lesion is suspected or found the individual will need a colonoscopy eventually. There is also an issue of radiation exposure and therefore colonoscopy is still regarded as the investigation of choice. MRI scanning is also valuable. It is particularly useful in detecting small bowel Crohn's disease, especially in parts where the colonoscope is unable to reach. A modified way of performing an MRI with the ingestion of a polyethylene glycol drink allows imaging of the small bowel with contrast (magnetic resonance enterography; MRE). This will pick up areas of intestinal stenosis caused by inflammation and also fissures and ulcerations of the mucosa. MRE also gives a good impression of the thickness of the bowel, another indication of infiltrative or inflammatory condition. A standard CT of the abdomen is also a valuable investigation. It has the advantage of being somewhat cheaper than MRI and it can show quite a lot of detail. It will also show the presence of abscess formation or diverticular disease of the colon. Finally, if lymphoma is suspected, a CT scan of the abdomen would pick up associated lymphadenopathy, which usually is generalized and may be associated with splenic enlargement (Figs. 1.17 to 1.21).

Is it Volvulus or Intussusception?

Occasionally, patients may have intermittent severe pain due to intermittent volvulus. If volvulus is suspected, a plain X-ray is often very helpful (Fig. 1.22). Gastric volvuluses can be picked up and are often associated with a large diaphragmatic defect and a chest/upper abdominal film would be quite revealing. A volvulus affecting the sigmoid would present with constipation and abdominal distention and often a large “coffee bean” shadow on the abdominal film is seen (Fig. 1.23).

Fig. 1.18: Colonoscopic findings of deep fissuring ulcers with skip lesions favor a diagnosis of Crohn's disease.

Fig. 1.20: Extensive mucosal inflammation and edema: This patient has raised peripheral eosinophil count and should alert the clinician to possible eosinophilic enteritis.

Both problems may be intermittent and may present acutely as a surgical emergency but sometimes may be chronic and persistent or even be asymptomatic (Figs. 1.24A and B).

Is it Mesenteric Ischemia?

Mesenteric Ischemia should be considered in an older patient. It can present acutely as an area of bowel infarction. This can occur after an episode of hypotension when areas of vascular watershed like the splenic flexure of the colon can become ischemic. Patients may present with pain, rectal bleeding with or without diarrhea. Acute intestinal infarction can also occur in patients with embolic disease like atrial fibrillation. Atheromatous diseases tend to present with chronic intestinal ischemia with a chronic pain often 18associated with food and eating, sometimes referred to as intestinal angina. These patients therefore reduce their food intake and can lose weight quite dramatically. A good history is the key. It is strongly associated with smoking and diabetes and they often have evidence of arteriopathy elsewhere, like peripheral vascular disease or ischemic heart disease. It can be extremely difficult to diagnose, CT may show calcified vascular atheroma. MRI angiography can be helpful in this situation, confirmation and treatment requires direct angiography and angioplasty can be attempted.

Figs. 1.24A and B: Gastric volvulus. (A) The gastrografin meal shows a gastric volvulus flipped along its axis (organo-axial volvulus); (B) CT image shows the same.

Is it Diverticular Disease?

Diverticulosis of the colon is extremely common. Like gallstones, it is easy to attribute symptoms to diverticular disease but they may not necessarily be the cause of the patient's complaint. Diverticular disease is easily picked up on barium enemas, abdominal CTs or colonoscopy. Typically, diverticulosis causes few symptoms. However, when they get inflamed (diverticulitis) 19they can cause discomfort, pain and altered bowel habit. The pain is usually in the left iliac fossa as the commonest site of diverticular disease is in the sigmoid colon.

Is there an Underlying Metabolic Disease?

Metabolic diseases are rare. However, physicians should always be alert to a possibility in unusual presentation of organic diseases suspected and none found. Hypercalcemia and porphyria are metabolic diseases that can present as abdominal pain. In the case of hypercalcemia, serum calcium is easily checked by chemical profile. Hence, it is important to cast an eye on the calcium level when attending to a patient with abdominal pain. In hypercalcemia, pain can be caused by acute as attacks of acute pancreatitis or chronic pain due to dyspepsia or ulcer disease caused by hypersecretion of acid. This is due to the raised serum gastrin found in patients with hypercalcemia. The helpful aide memoire: “stones, bones and abdominal groans” summarizes hypercalcemia with renal stones, bone lesions and abdominal pain. Hyperlipidemia syndromes may also present with acute abdominal pain because it can cause attacks of acute pancreatitis.

Porphyria can cause abdominal pain. Acute intermittent porphyria, porphyria variegata but not porphyria cutanea tarda, can cause acute intermittent episodes of severe abdominal pain rather than chronic pain. There may be neurological complications such as behavioral disturbances, epilepsy, coma or peripheral neuropathy. During an acute attack of hyponatremia; hypertension and uremia are common. Other rare causes of abdominal pain include lead poisoning, C1 esterase inhibitor insufficiency, familial Mediterranean fever and neurological conditions like multiple sclerosis and peripheral neuropathy. Abdominal pain is also a common problem in patients with longstanding diabetes. They are at increased risk of gallstones, duodenal ulcer disease, intestinal vascular insufficiency and pancreatitis.

A high index of suspicion and the specific diagnostic test is required to make the correct diagnosis.

Is there an Occult Malignant Disease?

If the patient remains unwell with persistent pain, there is always a lingering worry that malignant disease may have been missed. The next step would be a review of all the investigations carried out to date making sure that there are no gaps left unplugged. Abdominal CT scan is probably the best investigation to exclude intra-abdominal malignancies and if in doubt should be reviewed by an experienced radiologist. Colonoscopy remains the best investigation for colonic neoplasia but occasionally it may be missed because of a bad prep or incomplete examination. Hence, a review of the colonoscopy and a repeat procedure by an experienced endoscopist should be considered if there is a high degree of clinical suspicion. If there is still some doubt, then a “wait and 20see policy” or an interval CT scan, perhaps 2 or 3 months down the line would be helpful, but with modern imaging it is rare to miss lesions unless they are extremely small or elusive. Finally, in patients where the diagnosis remains elusive and the suspicion is still high, a laparoscopy may be considered, but it would be unusual to resort to such invasive measures (Figs. 1.25 and 1.26).

Is it Endometriosis?

Lower abdominal and pelvic pain associated with hemorrhagic phase of the menstrual cycle is suggestive of endometriosis. Up to 25% of these patients may have bowel involvement and that often results in abdominal pain. The endometriosis tends to occur on the serosal surface and bleeding into the gut is really quite rare. Endometriosis can cause stricture and adhesions and sometimes mistaken for neoplastic disease or Crohn's disease. 21Laparoscopy usually is diagnostic and treatment with cauterization is possible laparoscopically.

CONDITIONS CAUSING CHRONIC OR RECURRENT ABDOMINAL PAIN: NATURAL HISTORY AND MANAGEMENT

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Natural History

Irritable bowel syndrome should be considered as one of a group of functional GI conditions that occur throughout the elementary tract. It is by far the commonest of the functional GI diseases. It can be very varied in presentation and can mimic serious organic diseases. It is very troublesome to the sufferer and can be challenging to manage.

Symptoms: The cardinal symptom that most patients complain of being abdominal pain. There may be continuous dull ache but most frequently it is a colicky-type abdominal pain that comes as spasms lasting only a few minutes or several hours. The site of the pain can be very variable, often flitting, but sometimes predominantly in an area typically the left iliac fossa or the right iliac fossa. When asked to point where the pain is, patients often move their hands in a circular fashion over the abdomen suggesting a varied or diffuse site. Along with the pain, the two other principal symptoms are abdominal bloating/distention and a change in the bowel habit. This can vary from predominant constipation to predominant diarrhea or a mixture of constipation alternating with diarrhea. Definitions of IBS have been proffered and it can be quite difficult to pin down precisely. For the purposes of clinical trials, strict definitions are required and several have been devised. The Rome III criteria (Rome Foundation for Functional GI Diseases) included recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort for 3 days out of a month in the past 3 months associated with two or more symptoms which include:

- Improvement with defecation

- Onset associated with change in stool frequency

- Onset associated with change in stool form.

This definition is rather loose and all-encompassing and has since been replaced by Rome IV in 2017. NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) offered an alternative, simpler definition that is more suitable for everyday clinical use and the definition is:

Abdominal pain/discomfort relieved by defecation or associated with altered stool frequency/form plus 2 or more of:

- Altered stool passage

- Abdominal bloating/distention

- Symptoms made worse by eating

From a clinical point of view, the patients presenting with the classic pattern of abdominal pain associated with bloating and a change in bowel habit are usually easy to pick out and patients with predominant constipation or alternating constipation and diarrhea probably require no further investigation. However, patient with persistent diarrhea would probably benefit further investigation to detect cases of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, bile salt diarrhea and microcytic/collagenous colitis.

Psychology: Anxious obsessional patients are certainly more likely to consult a doctor if they develop IBS, but the psychological aspects of this condition are probably over emphasized. Many patients who are psychologically normal to have this syndrome. It is true that patients will often bring out stress as a major trigger for their symptoms. However, it would be a mistake if the physician overemphasized that aspect and deprive the patient of simple treatments that might improve their symptoms and overly focus on the psychological aspects. Suggesting that the condition is all in the mind is likely to upset the patient and create barriers between physician and patient.

Epidemiology: A survey has shown that over 14% of apparently healthy British subjects have IBS by the ROME 1 criteria. Furthermore, over half the patients attending British gastroenterology clinics have a predominant functional bowel problem. Although 65% are women, an increasing number of young men also suffer from this condition. In many of these patients, the problems are longstanding and when questioned, these patients would often have a very long history starting from early adulthood or childhood.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: This syndrome has many complex and contributory factors. Looking at the predominant symptoms in turn.

Abdominal Pain: The mechanism of abdominal pain is complex. There is good evidence that patients with IBS have increased visceral sensitivity. Inflating a balloon in the rectum of a patient showed that they experienced discomfort at lower volumes than normal subjects. There is also evidence that patients with IBS handle pain abnormally. This probably occurs at the modulation level in the spinal cord. In patients with postinfective IBS, there is also microinflammation and inflammatory cells may release pain causing chemicals at the nerve endings.

Bloating: Bloating is a very common symptom of IBS. Its etiology is also quite complex. There is evidence for abnormal gas handling. The tone of the bowel may be altered causing gas to be trapped in parts of the bowel and there may be altered gas production as well. Altered gas production may be due to bacterial fermentation processes. In patients where there is small bowel bacterial overgrowth, there is increased gas production in the small bowel. Patients who are intolerant of carbohydrates and also with celiac disease may also have abnormal gas production due to poorly digested sugars fueling colonic bacterial fermentation. Furthermore, ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates 23is also a possible source of gas. Patients with slow gut transit found in those with predominant constipation will also get abdominal distention from fecal loading. Finally, some hormones, particularly estrogens, can cause abdominal bloating. However, all the causes of gas production above does not account for the degree of distention that many patients display. It also does not account for how quickly the distention can occur and regress in the course of a day. It is now known that the most important contributor to bloating is phrenic dyssynergia. This occur when the diaphragm is contracted unconsciously, and simultaneously the abdominal wall muscles to relax. The cause for this is still unknown (Fig. 1.27).

Change in Bowel Habit: A change in bowel habit is characteristic of IBS. Thus, IBS may be classified as being IBS-D when there is predominant diarrhea, IBS-C when there is predominant constipation and IBS-M when there is an alternating or mixed picture. The etiology is complex and probably multifactorial. The change in motility of the gut may be a result of delayed gastric emptying, small bowel or colonic transit changes. This is often triggered by food or emotion. In a number of patients, there is also evidence of small bowel bacterial overgrowth.

The stool type correlates very well with gut motility and the Bristol Stool Chart has become a very useful visual aid in clinics for patients to point out which type of stools they have. Stool types 1 and 2 (Fig. 1.28) are associated with constipation and the gut transit is slow, whereas patients with Bristol types 6 and 7 have rapid gut transit and diarrhea.

Postinfective Irritable Bowel Syndrome: In a number of patients presenting with IBS, there is a clear history of an infective episode prior to the onset of IBS symptoms. There will be a history of some kind of infectious diarrhea whether or not a pathogen becomes cultivated. During the acute episode, there is usually diarrhea plus vomiting, rather than diarrhea alone.

Fig. 1.27: Bloating: It is a combination of gas as diaphragmatic contraction and relaxation of abdominal wall muscles.

The patients then start having episodes of the typical IBS that lasts long after the acute episode. There is a predominance of diarrhea (IBS-D) as opposed to the constipation or alternating type. There is often a higher anxiety score prior or during the infection. Patients often acquire the infection while travelling, often on holiday or away from home.

Algorithm for Diagnosing Irritable Bowel Syndrome: It is important to make a firm diagnosis of IBS early without recourse to complex and unpleasant investigations. NICE has issued a set of guidelines that are quite helpful. If the patients do not have alarm symptoms and have the typical symptoms outlined above, then a firm diagnosis of IBS can be made. The alarm symptoms include:

- Age (>40)

- Strong family history of colorectal cancer/IBD

- Rectal bleeding

- Anemia

- Weight loss

- Abdominal mass.

In this group, only a simple noninvasive test is required. Blood tests including a full blood count, biochemistry, CRP and thyroid function test along with celiac antibodies can be carried out. Stool tests, including fecal calprotectin and culture if there is the reason to suspect an infective cause. If diarrhea is predominant, a hydrogen or methane breath test can be very helpful. This detects the presence of small bowel bacterial overgrowth that ferments glucose or lactulose and releases hydrogen or methane in the breath. The test is simple and relatively cost-effective. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin is emerging as a very helpful test in this situation. Calprotectin and lactoferrin are released by inflammatory cells into the GI tract and this is excreted in the feces and easily detected. When there is inflammation, the level of fecal calprotectin 25rises exponentially. Laboratory standards vary, but any fecal calprotectin over 50 µg/g of feces is usually indicative of possible inflammatory bowel disease. However, a negative calprotectin does not exclude other organic diseases or indeed Crohn's disease in remission. A simple algorithm is shown in Figure 1.2.

Abnormal Bile Salt Handling: Nearly 30% of patients with IBS have been found to have abnormal bile salt handling. When bowel salts are not reabsorbed in the terminal ileum then some gets into the colon and that irritates the colon and can cause diarrhea-predominant symptoms. It is possible to carry out a SeHCAT scan. This, however, can be quite expensive. Empirical treatment with cholestyramine is safe and cheap and should be tried in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Often doubt still exists as to whether or not the patient has inflammatory bowel disease and probably the single most useful investigation in this situation is to perform a colonoscopy. For patients with diarrhea-predominant symptoms, inflammatory bowel disease can be difficult to exclude. Patients with microcytic and collagenous colitis can be very difficult to diagnose without endoscopic examination and may have negative fecal calprotectin and ultimately can only be diagnosed with biopsies, particularly of the right colon.

Management

Reassurance: The most important part of management of IBS is reassurance. Make a firm diagnosis and explain that it is a benign condition. The mechanisms of pain and altered bowel habit in a healthy intestine should be explained simply and clearly to the patient. It should be made clear that the doctor understands the severity and genuine nature of the patient's symptoms and that the patient can be reassured that the condition is not harmful and the frequency and severity of symptoms would diminish with time. Treating the patient dismissively as a neurotic will lead the patient to assume that symptoms have not been taken sufficiently seriously. This will increase any cancer phobia and the patient will almost certainly seek a second opinion.

Having established a rapport, the physician should look at exploring some of the triggers. If there is evidence of an infective trigger, then probiotics may be proffered although clinical trial evidence for its use is sketchy. If there is a degree of stress or anxiety involved, that should be addressed at a suitable time. Other psychological treatments like hypnotherapy and counseling have a place if available.

Dietary Advice: Dietary advice or dietetic referral may be helpful. It is directed at specific symptoms.

Constipation: Patients with predominant constipation should be encouraged to eat more foods containing soluble fibers. This is found in many foods like fruit and cereals.26

Diarrhea: Diarrhea can be more difficult to treat with dietary measures. Avoidance of certain foods like dairy and gluten may be important. Even patients without celiac disease may have poor carbohydrate handling and gluten intolerance and it is well worth trialing them on a gluten avoidance diet.

Bloating: Foods that produce a lot of gas are the ones that are fermentable. A group of foods known as FODMAP (Fermentable Oligo-Di-Mono-saccharides and Polyols) are shown to produce more gas and therefore abdominal distention. Avoidance of these foods can be difficult as they are very varied but a session with a dietitian can be very helpful.

Pharmacological Treatments: Once a patient is reassured that the condition is benign, it is important then to explain that you have means of treating the specific symptoms. Abdominal pain can be treated with antispasmodics like mebeverine, hyoscine and alverine. If the pains are spasmodic and episodic then patients can have these drugs on demand rather than on a maintenance fashion. If the pain is more constant then treatment with a small dose of a tricyclic like amitriptyline has been shown to be effective although tricyclics tend to cause constipation and therefore best avoided in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel. Conversely, tricyclics can be very helpful in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS. An alternative to tricyclics are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). They tend to cause diarrhea probably a better drug to try on patients with constipation-predominant IBS. It is important to emphasize that you are using the drugs to control the symptom not because you think they are depressed as such.

Newer drugs have been recently evaluated for use in IBS with constipation. For IBS-C linaclotide have recently been introduced. A longer discussion of these drugs on constipation is in the Chapter 4. For IBS-D, symptomatic treatment with loperamide is helpful and new agents like eluxadoline have been recently approved for this indication. Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed antibiotic, has also been approved for IBS-D (see Chapter 3).

Patients with evidence or suspicion of bile salt malabsorption could be given a trial with cholestyramine. Bile excretion is maximal in mornings, so this is best given first thing in the morning, 30 minutes before breakfast. If there is evidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, antibiotic therapy, notably with rifaximin, could be given.

Duodenal Ulcer

Natural History

Diagnosis: The principal means of diagnosing duodenal ulcer disease is endoscopy. However, if patients present with dyspeptic symptoms it is not unreasonable to perform a test for H. pylori on the onset. The noninvasive 27methods of testing for H. pylori are cheap and that could be serology, breath testing or fecal antigen testing. The latter has increasingly gained acceptance as being both sensitive and specific. The presence of H. pylori in a symptomatic patient would justify H. pylori eradication. This “test and treat” method has gained general acceptance in recent years.

Symptoms: The symptoms of duodenal ulcer disease can be rather non-specific. Duodenal ulcers may be completely asymptomatic and it is not uncommon for patients to be admitted to hospital with a bleeding ulcer and give no history of previous dyspepsia. The most common symptom is epigastric pain that wakes the patient at night and periodic pain. Periodic pain refers to relapses of pain lasting several days or weeks interspersed with pain-free periods for weeks or months. Less reliable association is relief of pain with antacids or food. Major complications of duodenal ulcers are perforation and bleeding and in the elderly and patients with multiple comorbidities like cardiac, renal failure and malignancy, it carries a significant mortality rate.

Epidemiology: Previous epidemiological studies have shown that as many as 9% of women and 12% of men have been told they have a diagnosis of duodenal ulcer disease at some point. However, the discovery that H. pylori is a major cause of duodenal ulcer disease has led to eradication of the bacteria. This has completely altered the natural history of the disease from a recurrent condition to permanent cure. Furthermore, as the prevalence of H. pylori infection decreased in many Western nations, so has the prevalence of duodenal ulcer disease. However, there is an increase in incidence of nonsteroidal-induced peptic ulcer disease particularly in elderly patients. Smoking is strongly associated with duodenal ulcer disease as is alcohol.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: H. pylori infection and NSAIDs are the main etiological causes for duodenal ulcer disease. The mucosa of the stomach and duodenum need to defend itself against the effects of pepsin and acid. Mechanisms in which there is increased acid and pepsin action and reduced defenses by the duodenal mucosa would result in mucosal ulceration and breakdown. Defects in the healing and repair mechanisms are also contributory factors. Smoking and stress can elevate basal acid output, reduce mucus synthesis and inhibit healing.

Drugs like the anti-inflammatory drugs and aspirin cause ulceration either by direct toxic effects or inhibit prostaglandin synthesis by binding on cyclo-oxygenase (COX) active site (specifically COX-1). Aspirin even in low doses can cause ulceration by direct toxic chemical effects on the mucosa itself. Nonsteroidals drugs, however, tend to act by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. Prostaglandin depletion causes an increase in acid secretion, 28decreased mucin production and a decrease in bicarbonate secretions, all factors vital in promoting ulcer formation. Prostaglandin is also important in epithelial cell healing and therefore nonsteroidal drugs also reduce the ability of the mucosa to repair itself. Additionally, the analgesic effects of non-steroidal drugs may account for the fact that many nonsteroidal-induced duodenal ulcer disease remain silent and may not present until bleeding or perforation occurs (Fig. 1.29).

Helicobacter pylori: H. pylori remains the major cause for duodenal ulcer disease and worldwide it is a massive health problem. It is strongly associated with duodenal ulcer disease but the most convincing evidence is the fact that when eradication of the bacteria is successfully achieved a cure results. However, the bacterium is very common and the majority of people harboring this bacteria in the stomach do not have duodenal ulcer disease or come to any apparent harm. The bacterium is a gram-negative rod and resides in the deep portions of the mucus, generally in the gastric mucosa. It is uniquely adapted to this hostile environment. It has multiple flagella that helps in motility and adhesion and produces very strong urea enzyme. This produces ammonia from urea which is alkaline and helps to neutralize any acid diffusing into the mucus layer.

The infection is probably acquired during childhood and spreads in areas and times of overcrowding. Initially, the bacterium tends to inhabit the antrum of the stomach and over time tend to migrate proximally. Apart from duodenal ulcer disease, H. pylori infection is credited to cause gastric ulcers, MALT lymphomas and gastric cancer. It is still not understood as to how the bacterium can cause the diverse pathology and yet, in a large number of individuals, it causes no symptoms or pathology at all. It is likely to be a combination of bacterial and host factors. The bacteria may have genetic determinants that result in increased pathogenicity. This includes 29its ability to produce certain enzymes like VacA and CagA or may have adhesins which facilitate attachment of the bacteria to the gastric epithelial cells. Amongst host factors may be the subject's ability to mount an inflammatory response and the specific site of the stomach where the bacteria tend to colonize.

Patients who predominantly have antral inflammation would lead the antral G cells to produce high levels of gastrin via the loss of negative inhibition from the D cells in the antrum. The result is an elevated gastrin level that stimulates the acid secreting parietal cell to secrete more acid. Patients who have predominantly body and fundus infection with H. pylori may find that the parietal cells themselves get affected and acid level output may actually be reduced. This may lead, in the long term, to chronic atrophic gastritis eventually leading to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and leading to gastric cancer. In the majority of patients with pangastritis, the infection tends to be non-pathogenic and therefore the bacterium inhabits the individual without producing any symptoms or disease (Fig. 1.30).

Management of Duodenal Ulceration

The management of duodenal ulcers has altered dramatically over the last 30 or 40 years. Operations frequently performed for duodenal ulcers in the past have given way to highly effective acid suppressing drugs like H2 antagonists and then followed rapidly by even more powerful acid suppressants like PPIs. H. pylori eradication has changed the natural history of the disease. However, increased bacterial resistances to antibiotics have hindered effective H. pylori eradication in many parts of the world.30

H2 Antagonists and Proton Pump Inhibitors: H2 antagonists like cimetidine and ranitidine are safe and effective drugs for reducing gastric acid secretion and are now found in many over-the-counter medications for dyspepsia. They do heal duodenal ulcers by suppressing acid by inhibiting the H2 receptors, one of the three receptors that cause the parietal cell to secrete acid. The other two receptors are acetylcholine receptor and gastrin receptor. Hence, it only partially inhibits the excretion of acid. The final pathway is the migration of the “proton pump” which is ATPase. This migrates to the canaliculus membrane and the pumping of a hydrogen ion (Proton) accompanied by potassium chloride that leads to the production of hydrochloric acid. This is pumping against a huge concentration gradient and acquires energy that is supplied in the form of the breakdown of ATP into ADP.

Inhibitors of the proton pump include omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole. Thus, almost complete blockage of acid secretion is the result. These drugs also have a long biological life as the inhibition is irreversible and parietal cells have to manufacture new proton pumps to replace those blocked. Ranitidine in clinical trials has shown to heal up to 70% of duodenal ulcers at 8 weeks whereas PPIs would heal duodenal ulcers at > 90% at 8 weeks. However, unless the underlying cause for the ulcers (e.g. H. pylori and nonsteroidal drugs) is removed then the ulcers would tend to recur (Fig. 1.31).

Fig. 1.31: Parietal cell function: The gastric parietal cells are the producers of acid in the stomach. Gastrin acetylcholine and histamine receptors are present in the inner membrane where hormonal (gastrin), neural (vagus nerve releasing acetylcholine) and inflammatory (histamine) stimuli activate the proton pump ATPase. Inhibition of this enzyme stops parietal cell acid production.

Anti-Helicobacter Therapy: Eradication of H. pylori will result in curing of H. pylori-associated duodenal ulcer disease. As this accounts worldwide for the majority of duodenal ulcer cases effective H. pylori eradication is much sought after. The typical regime would be a “triple therapy,” which comprises of a PPI like omeprazole or lansoprazole with two antibiotics typically a combination of either clarithromycin or amoxicillin or metronidazole or tinidazole. The treatment is usually carried out for 14 days. Shorter regimes tend to be less effective and promote bacterial resistance. Even with 14-day triple therapy eradication may not exceed 70% and may be even lower in parts of the world where antibiotic resistance is common. Hence, in refractory cases other treatment strategies have been sought. One strategy is quadruple therapy with the addition of bismuth in the form of tripotassium dicitratobismuthate. Other regimes have also been recently trialed. One particular promising regime is “sequential therapy” that usually takes the form of 5 days of lansoprazole and amoxicillin followed by 5 days of lansoprazole, clarithromycin and metronidazole.

Failure to Heal: A repeat endoscopy to check for healing is not usually necessary. Effective H. pylori eradication can be checked either by using urea breath tests or fecal antigen tests, both of which are equally reliable. However, if the patient remains symptomatic it may be necessary to re-endoscope such patients. If patients are compliant with treatment and H. pylori eradication is confirmed then one would also have to question whether patients have been taking aspirin or nonsteroidal agents. Rare conditions such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome should also be considered. Effective treatment with H. pylori eradication should result with an effective cure. However, in some patients the H. pylori may be resistant to therapy. In a few patients, it would be necessary to be placed on maintenance therapy with PPIs.

Surgery: Surgery for duodenal ulcer disease thankfully is extremely rare nowadays. Operations are usually now reserved for complications such as bleeding and perforation. The operations performed are mainly of historic interest but there remain some patients from the “pre-Helicobacter discovery era” who may have had such procedures carried out on them (Fig. 1.32).

Duodenitis

Duodenitis is often reported in endoscopy reports for endoscopies carried out for dyspeptic symptoms. However, there is a very poor correlation between symptoms and endoscopic appearances. Even endoscopic and histological appearances are poorly correlated. Many asymptomatic patients may have duodenitis as incidental endoscopic findings. However, it is clear that H. pylori infection in the duodenum often leads to gastric metaplasia. This occurs when gastric type mucosa starts proliferating in the duodenum.32

Gastric metaplasia may also be caused by increased acid secretion. Non-steroidal drugs and aspirin are also implicated in causing duodenitis. Duodenitis is also strongly correlated with smoking and patients with poor nutritional intake.

When widespread duodenal inflammation occurs, it is also important to consider Crohn's disease; celiac disease; Whipple's disease and small bowel lymphoma. Biopsies would be indicated if the endoscopist is unsure of the exact pathology or if these conditions are suspected. Usually, however, the inflammation is mild, confined to the first part of duodenum and is usually of little consequence to patients.

Non-ulcer Dyspepsia/Functional Dyspepsia

Natural History

The term “non-ulcer dyspepsia” is unsatisfactory with different meanings to different clinicians. The term is now largely replaced by the more useful term of “functional dyspepsia”. Fundamentally, it is presence of symptoms, such as:

- Epigastric pain

- Nausea

- Bloating

- Belching

- Heartburn

- Early satiety.

When endoscopy is carried out it is usually normal and is thus regarded as a functional condition. There is evidence of poor pyloric relaxation and gastric emptying and there is also evidence of visceral hypersensitivity with pain or intolerance when the stomach is distended with fluid.

Management

Due to variety of symptoms and the benign nature of the condition treatment is largely symptomatic. However, it is important to exclude H. pylori infection and if H. pylori is found then it is reasonable to give a trial of H. pylori eradication as previously discussed.

The management of functional dyspepsia includes the following:

- If a patient has endoscopy negative upper abdominal pain and no other organic causes found either through history or by ultrasound then a diagnosis of functional abdominal pain should be made and treatment is more in line with IBS with efforts directed to control of pain and bloating. Apart from tricyclics, prokinetic agents like prochlorperazine and metoclopramide can also be helpful in this situation. The latter two drugs carry a risk of extrapyramidal side effects. Due to risks of cardiac complications domperidone use in this condition is not encouraged.

- If heartburn is a predominant symptom, then the use of antacids and other antireflux treatments is perfectly reasonable. Use of PPI has also been shown to marginally improve symptoms in this group of patients. Even in the absence of endoscopic appearance of esophagitis, reflux can occur.

- Diet would also play a role. Diets containing high levels of fat tend to inhibit gastric emptying and can encourage symptoms like bloating.

Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome

Natural History

In Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, there is duodenal ulceration due to increased acid production. The ulcers are multiple and usually in the distal duodenum and even in the jejunum. This syndrome is rare and probably accounts for <1 in 10,000 of all patients with duodenal ulceration but it is often left undiagnosed.

Gastrin is produced by the G cells of the gastric antrum. In Zollinger–Ellison syndrome, excessive gastrin is produced by non-beta islet cell tumors of the pancreas or duodenum. This is not under the natural feedback mechanism and leads to constant over stimulation of the parietal cells that leads to overproduction of acid. This results in hypertrophy of the gastric body and a high basal acid output. The acid is dumped into the duodenum and upper duodenum and causes ulceration.

The tumor is malignant in about 65% of patients and about 25% of tumors are sited in duodenal wall and may be very tiny and difficult to diagnose. 34However, the majority of the tumors will be found in the duodenum or the neck of the pancreas or even the porta hepatis.

Acid also inactivates pancreatic lipases and results in fat malabsorption. Diarrhea is therefore a very common symptom along with the classic symptoms of duodenal ulceration.

Diagnosis of Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome

Fasting gastrin levels is the best screening test for Zollinger–Ellison syndrome. It is also important to check the calcium levels as it may be part of a multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 1 syndrome (MEN1). Gastric acid secretion tests are rarely performed these days. In doubtful cases, a provocation test using secretin and a measurement of serum gastrin can also be helpful to make the diagnosis.

Imaging with CT scan would be necessary to locate the tumor but it is only possible to locate the tumor in 50% of the patients. Endoscopic ultrasound can also be very useful. Frequently tumors are <1 cm and easily missed on scanning. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (octreotide scan) is the best imaging modality. It uses radiolabeled somatostatin analog that binds to the receptors found on these tumors (Fig. 1.33). Finally, endoscopy which shows unusually severe ulceration of duodenum should alert the clinician to consider this diagnosis.

Management of Zollinger–Ellison Syndrome

The management depends on the operability of the primary secreting tumor. If it is operable then it would be considered curative. Medical therapy for controlling gastric acid output is achieved using PPIs often at higher than usual doses. In patients where surgical resection is not possible, palliative therapy with chemotherapy, interferon, and octreotide may be helpful but the response to these agents in most studies has been poor.

Fig. 1.33: Octreotide scan. This shows a hot spot in the pancreas from a neuroendocrine tumor. Similar hot spot may be be seen in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.

Benign Gastric Ulcer

Natural History

Symptoms: The symptoms of benign gastric ulceration are highly variable and can often be vague. Pain is usually but not always present in the upper abdomen. Usually the pain is less prominent in benign gastric ulceration than in the duodenal ulcers. Response to food is also variable, while half of the patients may get relief from eating another third may actually have pain exacerbated by food. Other symptoms include epigastric discomfort, belching, nausea and water-brash (a sudden outpouring of saliva). Patients may present with complications of gastric ulcers like bleeding and weight loss is not an uncommon symptom making it difficult to distinguish between malignant and benign conditions from symptoms alone.

Epidemiology: Gastric ulcers are less common than duodenal ulcers. In the United Kingdom as in most of Western Europe and North America, the overall incidence is decreasing but with an increasingly elderly population and a high use of nonsteroidal drugs and aspirin the incidence of complicated gastric ulcers have remained fairly constant.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: Gastric ulcers like peptic ulcer may be associated with Helicobacter infection. This is particularly true for ulcers in the prepyloric area and antrum. In the elderly population in particular, nonsteroidal agents are a major cause for gastric ulcers. Typically, they cause ulcers in the lesser curve of stomach and antrum at the junction between the antral and body-type mucosa. The inhibition of prostaglandins is likely to be the major contributory factor to these ulcers. Other contributory factors include smoking, genetic factors and poor diet. Steroid therapies are often blamed for ulcers but there is no evidence that it increases the risks of gastric ulcers but it may certainly delay healing. Ulcers associated with stress tend to be the superficial variety and can occur in severe trauma, burns (Curling's ulcers) and acute sepsis. Prophylactic use of acid suppression with PPIs may prevent these ulcers from forming.

Management

Establish that the Ulcer is Benign: The first priority is always to establish that the ulcer is truly benign. This will require endoscopy with biopsy and possibly brush cytology if available. Biopsy should be performed even if it looks benign and after treatment at an interval of about 6–8 weeks endoscopy should be repeated to ensure complete healing. Ulcer that fails to heal adequately should be treated with suspicion.

Drug Therapy: H. pylori is implicated in about two-thirds of gastric ulcers and if it is detected eradication therapy is indicated. Details of eradication therapy 36have been discussed earlier. Gastric ulcers can take longer to heal than duodenal ulcers particularly if they are very large. Treatment with PPIs is effective and the ulcers should be reviewed with further endoscopy after 6–8 weeks of treatment to ensure complete healing. If in doubt further biopsies should be performed.

Avoidance of nonsteroidal agents would be important in patients who have nonsteroidal-induced gastric ulcers. Aspirin and antiplatelet drugs like clopidogrel should be reviewed. However, these are often prescribed for major cerebrovascular and cardiovascular indications like stroke and ischemic heart disease. The morbidity and mortality from these conditions may outweigh the risks of the gastric ulcers and therefore coprescription with PPI and aspirin together is acceptable and often results in lower overall morbidity and mortality.

Gastritis

Strictly speaking, gastritis should refer to histological evidence of inflammation of the stomach. Different classification exists. It can be a clinical classification based on whether it is acute gastritis or chronic gastritis, or one based on histological or endoscopic appearances, or one based on its etiology. As a result, there is no universally accepted classification system despite attempts like the Sydney Classification. Gastritis is also often reported by endoscopist based on endoscopic appearance of inflammation or redness. However, there is often no correlation between an endoscopic appearance and underlying histology or etiology of the gastric mucosal inflammation. Additionally, inexperienced endoscopists may report vascular abnormalities such as gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) as “gastritis” (Fig. 1.34).

Fig. 1.34: Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) gives an appearance not unlike a watermelon and sometimes referred to as watermelon stomach. It is often misdiagnosed as “gastritis” by inexperienced endoscopists.

Probably the best way of classifying gastritis is probably by its etiological origin.

Acute Erosive Gastritis

Acute erosive gastritis usually affects the antrum but sometimes the corpus of the stomach and occurs after major trauma, burns, sepsis, renal failure and also ingestion of alcohol, aspirin or ingestion of toxic substances. It is often asymptomatic but can cause acute upper GI bleeding. Its cause is unknown but probably related to high acid and poor cytoprotection in such patients. Management of the underlying pathology is obviously the key to prevention of acute erosive gastritis along with prophylactic use of PPIs.

Chronic Gastritis

Chronic gastritis can be broadly divided into two forms, either infectious origins or noninfectious conditions (Table 1.2).

Helicobacter-associated Chronic Gastritis

Helicobacter pylori is the principal cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma and primary gastric lymphoma. It has a worldwide distribution and rates of infection vary between countries. The effects of H. pylori infections vary according to the site of colonization of the bacterium. There are both bacterial factors and host factors that would also decide on the final outcome of the H. pylori infection. Gastritis is almost universal. It may affect the whole stomach (pangastritis), predominant antral infection (antral gastritis) or a body type infection (corpus gastritis). When gastritis affects predominantly the antrum of the stomach then gastrin secretions are abnormally high especially with meal stimulated release of gastrin. These patients would tend to develop peptic ulcer disease.

|

Helicobacter pylori pathogenicity is decided by certain inherent virulence factors in the bacterium. Strains that produce a protein CagA associated with greater risk of developing gastric cancers and peptic ulcers.

Some patients develop a multifocal atrophic gastritis pattern where the infection of the corpus of the stomach eventually leads to a pattern of gastric atrophy with loss of gastric glands and eventually replacement of gastric glands by intestinal-type mucosa (intestinal metaplasia). This will eventually develop into dysplasia and gastric cancer. Because of gastric atrophy, the acid levels tend to fall and carcinogenic agents such as nitrosamine are not neutralized by acid.

The majority of patients with H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis, however, remain asymptomatic. Only a small number will develop duodenal ulcer disease and gastric cancer (Figs. 1.35 and 1.36).

39

Other Infectious Gastritis

Granulomatous gastritis is a rare condition that may be caused by tuberculosis or Cryptococcus. Immunocompromised patients may occasionally acquire cytomegalovirus or mycobacterial infections involving Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI) species.

Gastritis Caused by Autoimmune Causes

Patients with autoimmune gastritis may have elevated antibodies such as an intrinsic factor and parietal cell antibodies. Two types of atrophic gastritis have been identified:

- In type A gastritis, the fundus is primarily affected resulting in reduced acid secretion. This causes the hyperplasia of gastrin-producing G cells and results in hypergastrinemia.

- In type B gastritis, the antrum is primarily affected and patients have normal serum gastrin.

Atrophic gastritis can be as a result of H. pylori infection when the H. pylori causes a pangastritis or a corpus gastritis. Thus, infection must be excluded by fecal antigen testing or any other readily available tests.

Atrophic gastritis may result in lower gastric acid production and may result in increased risk of gastric cancer. Atrophy of parietal cells also results in reduced production of B12 and development of B12 deficiency and pernicious anemia.

In terms of diagnosis, the endoscopic appearance of an atrophic stomach can be quite obvious with lack of rugal folds and biopsies would also be helpful in making the diagnosis.

Eosinophilic infiltration of gastric mucosa would result in eosinophilic gastritis. This condition is rare although it is increasingly being diagnosed. There may be a peripheral blood eosinophilia and they are sometimes associated with asthma and other allergic conditions. Patients may present with abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea or even ascites. Large antral folds may simulate other infiltrative processes like lymphoma and therefore biopsies are usually required to make a diagnosis. Patients may present with gastric outlet obstruction due to edema of the pylorus and infiltration of the antrum of the stomach (Fig. 1.37).

Biliary or Alkaline Reflux Gastritis (See Fig. 1.6)

Bile reflux causes a reddening appearance of the stomach on endoscopy. It is almost invariable as a consequence to partial gastrectomy and is termed biliary gastritis. It has a specific histological appearance characterized by foveolar hyperplasia.

Other Rare Gastritis

Hypertrophic gastritis or Ménétrier's disease is a very rare condition in which the fundic glands are replaced by a hypertrophic epithelium and forming massively enlarged mucosal folds. There is variable degree of inflammation.40

Figs. 1.37A and B: Eosinophilic gastritis. CT image (A) shows thickened gastric antrum correlating with the endoscopic image (B) of the same patient.

Patients may present with pain, vomiting, bleeding or signs of hypoalbuminemia, which results from excessive protein loss as mucous is shed from the gastric mucosa. Other rare causes of gastritis include sarcoidosis, granulomatous gastritis and lymphocytic gastritis.

Management

Acute Erosive Gastritis: Acute erosive gastritis may cause bleeding, requiring resuscitation and even emergency surgery. More usually, the bleeding can be controlled endoscopically and if nonsteroidal drugs are used, then they should be stopped and PPIs initially intravenously followed by oral PPI may be indicated. Very ill patients with septicemia shock, renal failure or hepatic failure may also develop acute ulcers, which may require PPI prophylactically.

Atrophic Gastritis: Atrophic gastritis may result in B12 deficiency so parenteral B12 replacement is required. If the atrophic gastritis is a result of H. pylori infection eradication of H. pylori would be wise.

Eosinophilic Gastritis: Eosinophilic gastritis usually responds very rapidly to corticosteroids, which may initially be necessary to give intravenously but that can easily be followed by a short course of oral prednisolone, usually starting with a dose of 30 mg and reducing over a week or so. Elimination of specific food allergies, use of leukotriene inhibitors montelukast or zafirlukast may also be helpful. Patients may have recurrence of this condition and may require a steroid sparing agent like azathioprine if they have repeated recurrence of this condition (See Figs. 1.20, 1.21 and 1.37).

Helicobacter-associated Gastritis: Treatment for Helicobacter-associated gastritis is H. pylori eradication, which has been discussed earlier. However, in asymptomatic individuals with H. pylori-associated gastritis, controversy exists as to whether they should have eradication or not. On balance with the 41hope of reducing the patients’ risk of developing gastric cancer, then H. pylori eradication is justified if found.

Biliary Reflux Gastritis: Biliary reflux gastritis responds well to bile chelating agents like cholestyramine. Aluminum hydroxide is also worth trying because it also has a bile acid–binding effect.

Carcinoma of the Stomach

Natural History

Symptoms and Signs: Gastric cancers are usually asymptomatic until invasion occurs through the submucosa and beyond. Hence, they often present late. The principal clinical features that they present with are weight loss, abdominal pain and vomiting. Weight loss is often the result of anorexia and pain on eating and early satiety (Table 1.3). Pain is often indistinguishable from those of peptic ulceration and may be relieved by PPIs and antacids or H2 antagonists. It usually takes the form of a vague upper abdominal discomfort often associated with a feeling of fullness. When the tumor is proximal to stomach there may be dysphagia as well. This may be from direct tumor obstruction or invasion of the nerve cells of the Auerbach plexus. The latter would cause pseudoachalasia syndrome with grossly dilated esophagus. Early satiety may be due to a diffuse form of gastric cancer (linitis plastica) where the stomach distends poorly because of the cancer. Distal tumors that block the pylorus or antrum will cause a gastric obstruction presenting with nausea and vomiting and sometimes hematemesis (Figs. 1.38 to 1.42).

A palpable mass may be found on examination. Signs of tumor spread may also be presenting features. Prominent left supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow's node) may be a sign of metastatic spread of gastric cancer and is also the most common sign of metastatic disease. When there are hepatic metastases then the liver may be often palpable and ascites may also be detected when there is peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Epidemiology: The incidence of gastric cancer in the United Kingdom and other developed countries is declining. Prevalence in the Far East and some Latin American countries remain very high. The increased risk in these areas is probably related to high rates of H. pylori infection. There is an encouraging decline in mortality from gastric cancer in the European centers (Fig. 1.43).

|

Fig. 1.39: Endoscopy: It appears unremarkable but the stomach was not distending with insufflation. This proved to be linitis plastica.

Fig. 1.40: CT scan of the above showed linitis plastica: a thickened stomach infiltrated with malignant cells.

Management of Gastric Cancer

When gastric, etc. cancer is suspected a prompt endoscopy should be made. When cancer is found, multiple biopsies and brush cytology should be carried out and the patient then fully staged. The commonest staging system used is the TNM criteria. It is based on the tumor (T) nodal (N) metastases (M). This is being revised at present moment and the physician should consult the American Joint Committee on Cancer website for details.

The imaging modalities required to adequately stage patients include:

Abdominal and Pelvic CT Scan: CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is very helpful in staging a disease. It will adequately pick up affected lymph nodes, liver metastases or ascites. However, lesions <5 mm may be missed by 44CT scanning. Patients with proximal gastric cancer should have a CT scan of the thorax as well (Fig. 1.44).

Fig. 1.43: Stomach cancer: 1971–2014. European age-standardized mortality rates per 100,000 population, UK.Source: cruk.org/cancerstats.

Endoscopic Ultrasound: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is helpful in gastric cancer staging. It is the most accurate method of staging the depth of tumor invasion. If the depth of invasion as evaluated at EUS shows that it is very superficial and not invaded submucosa then endoscopic resection may be possible. However, it is more useful as a tool for picking up tumors that have invaded the muscularis and also detects any local nodal involvement. In this situation patients may be offered neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy prior to surgery.45

Positron-emission Tomography Scan: Positron-emission tomography (PET) using a radio labeled (positron emitting) isotope of glucose (FDG). The FDG is taken up by tumor cells and is therefore valuable in detecting any distant metastases. However, patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis may be missed on PET scanning.

Staging Laparoscopy: If there is any doubt as to whether the tumor is operable or not then a staging laparoscopy is usually recommended. This is especially true if CT or EUS show more advanced tumors, particularly stage T3/T4 tumors but no metastases. Laparoscopy may be needed to establish operability.

Treatment of Gastric Cancer

If it is possible, surgical resection of the tumor is still the primary treatment. However, the treatment of gastric cancer is based on the staging of the tumor. A combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy; adjuvant chemotherapy and chemotherapy and surgery is available to the patient.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy refers to chemotherapy given before surgery to downstage the tumor. This is given in patients with bowel T3 or T4 tumors or patients with perigastric nodes.

Adjuvant chemotherapy refers to chemotherapy given along with surgery. The aim of adjuvant chemotherapy is to improve survival by eliminating any residual tumor after surgery.

The exact treatment protocol for each individual patient is usually discussed at the multidisciplinary team meeting where the imaging, histology and overall patient fitness are discussed. If the patient is fit for surgery, then every attempt is made to improve surgical outcome. Best treatments are still a subject for research and patients should be considered for entering many of the clinical trials that are currently running.

Prognosis and Screening

Successful surgical resection of an early gastric cancer carries a 90% 5-year survival rate. Invasive gastric cancers, however, have a very poor prognosis. In countries where there is high incidence of gastric cancer such as Japan, screening may be a viable option and pick up cases of early gastric cancer. This remains the best way of improving outlook of the disease. However, in countries where gastric cancer incidence is low risk, like in the United Kingdom, screening is not viable or a cost-effective option.

Gastric Lymphomas (Figs. 1.45 to 1.50)