Chapter Overview

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Boundaries

- 1.3 Teeth

- 1.4 Major Salivary Glands

- 1.5 Minor Salivary Glands

- 1.6 Tongue

- 1.7 Muscles of Mastication

- 1.8 Palate

- 1.9 Palatine Tonsils

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The mouth is comprised of the oral cavity and the oropharynx. The oral cavity is the area between the lips anteriorly and the palatoglossal arch posteriorly; the area further posterior to the arch signifies the entrance to the oropharynx. The mouth contains multiple structures from which relevant pathology may arise (Fig. 1.1), including the teeth, gingivae, tongue, floor of the mouth and the palate. It also has the openings of the ducts of the three paired major salivary glands. Basic knowledge of this anatomical area is essential for effective communication such as taking referrals from the emergency department or liaising with associated specialties. An overview of the types of pathology that may arise from the anatomical components of the mouth is listed in Table 1.1.

Examination of the Oral Cavity and Oropharynx

The oral cavity can be easily examined in clinic or by the bedside, requiring minimal equipment. Preferably, a head light should be used (a torch obviously occupies one hand; in dental clinic rooms a dental chair with a dedicated overhead light source is available).

The oral cavity should be sequentially examined by both inspection and palpation, grasping the tongue ideally with gauze so that the inferior and posterolateral aspects of it can be properly examined. The inferior aspect of the tongue contains superficial veins and its appearance can be of concern to some patients. Gloves should always be worn, enabling the floor of the mouth to be both inspected and palpated, as this is the most difficult part of the oral cavity to examine and is also a common site for presentations of oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Examination of the oropharynx in clinic can be achieved using a head light and a laryngeal mirror. Key areas to visualize are the tonsillar fossae (between the palatoglossus and palatopharyngeal muscles) and the posterior tongue as these may mask an underlying carcinoma. The rest of the pharynx requires flexible nasendoscopy, with the scope being passed through the nasopharynx to get a reliable, adequate view.

1.2 BOUNDARIES

Oral Cavity

The oral cavity is a box-shaped cavity that has a roof, floor and two lateral walls. It opens onto the face anteriorly through the oral fissure and is continuous with the oropharynx posteriorly. Two folds of muscle, the palatoglossus and pharyngeal arches, demarcate the junction between the oral cavity and the oropharynx. The roof of the oral cavity consists of the hard and soft palates. The floor is formed mainly of soft tissues, which include a muscular diaphragm and the tongue. The lateral walls (cheeks) are muscular and merge anteriorly with the lips.

The oral cavity is separated into two regions by the upper and lower dental arches consisting of the teeth and alveolar bone that supports them (Ellis and Mahadevan, 2010). The area found medially to the arches is the oral cavity proper and contains the tongue, palate, and floor of the mouth. The area lateral to the arches is termed the oral vestibule and is horseshoe-shaped, with its lateral boundary marked by the cheeks.

Oropharynx

The oropharynx is a three-dimensional structure bounded anteriorly by the anterior pillars of the pharyngeal fauces (the palatoglossus muscle), the circumvallate papillae (dividing the tongue into anterior two thirds and posterior third) and the junction between the hard and softpalate.

The posterior and lateral boundaries are formed by the muscular pharyngeal wall of the superior and middle constrictors. The superior extent is the level of the soft palate and the inferior extent is the level of the base of the tongue. The primary structures of note within the oropharynx that can potentially cause pathology are the base of the tongue and the palatine tonsils.

1.3 TEETH

Teeth are hard conical structures set in the dental alveoli (tooth sockets) of the upper and lower jaws and are utilized in both mastication and assisting in articulation (Koussoulakou, Margaritis and Koussoulakos, 2009). Humans have two sets of teeth, the deciduous (baby) dentition, which is sequentially replaced by the permanent (adult) dentition. There are 20 deciduous teeth that generally begin to erupt from the age of 3 months, starting with the incisors, and are fully erupted by the age of 2 years 6 months. There are 32 teeth in a full complement of adult teeth, with eruption starting with the first molars at the age of 6 years (6's at 6), followed by the central incisors and working progressively posteriorly.

A tooth has a crown, neck and one or more roots, giving each type of tooth a characteristic appearance (Fig. 1.2). The crown projects from the gingiva. The neck is the part of the tooth between the crown and the root. The root is fixed in the alveolus by the fibrous periodontal ligament.

Most of the tooth is composed of dentine, which is covered by enamel over the crown and cementum over the root. The pulp cavity contains connective tissue, blood vessels and nerves that are transmitted along the root canal and through the apical foramen. In a hospital setting, teeth and their associated pathology are most commonly visualized radiologically with an panorex, although its usefulness is limited for the more anterior teeth due to superimposition of the cervical spinal vertebrae.

Toothache is a common presenting intraoral symptom and knowledge of its derivation is required to correctly direct treatment. Sensation to the teeth comes from the lower motor neurons of the trigeminal cranial nerve; the inferior alveolar nerve (from the mandibular branch) travels within the mandibular canal and supplies the lower teeth (Fig. 1.3). It emerges from the mental foramen to provide sensation to the lower lip. The upper teeth are supplied predominantly by the superior alveolar nerves in conjunction with the incisive and palatine nerves (all derived from the maxillary branch). The upper teeth can be relatively easily anesthetized by infiltrating local anesthetic into the buccal vestibule aiming the needle tip toward the tips of the teeth. Extraction of the upper teeth requires further infiltration into the palatal mucosa adjacent to the tooth. Anesthetizing the more anterior mandibular teeth (premolars and forwards) can usually be achieved through infiltration of local anesthetic into the buccal vestibule in a manner analogous to that used for the upper teeth.

A nerve block of the inferior alveolar nerve is required to anesthetize the mandibular molar teeth and is performed by depositing anesthetic as close to the nerve as possible just before it enters the mandibular foramen. Extraction of the mandibular molar teeth requires infiltration of local anesthetic on the buccal aspect of these teeth in addition, blocking the buccal nerve in the process.

1.4 MAJOR SALIVARY GLANDs

Duct Orifices

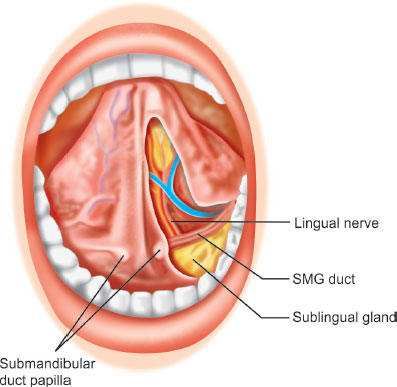

The orifices of the paired parotid gland ducts can be found in the buccal mucosa closely related to the upper second molar teeth. A small papilla is found adjacent to the orifice, and in health has the appearance of a0.5 mm linear opening. A stenotic papilla will be circular in appearance. The parotid papilla can be traumatized as it often lies between the upper and lower teeth and can get caught when chewing (du Toit and Nortjé, 2004). The submandibular (and sublingual) glands have duct orifices that lie under the tongue, either side of the lingual frenulum (Zhang, et al., 2010). The sublingual duct usually joins the submandibular duct rather than having a separate opening into the mouth. Massage of the parotid gland (and to a lesser degree the submandibular gland) should result in saliva being expressed from the duct in health and pathology can be indicated both by lack of saliva and pus being exuded from the duct orifice.

1.5 MINOR SALIVARY GLANDS

There are 800–1,000 minor salivary glands scattered throughout the oral cavity. They lie within the submucosa of the buccal, labial and lingual mucosa, the soft palate, the lateral parts of the hard palate and the floor of the mouth. They are 1–2 mm in diameter and unlike the major glands, they are not encapsulated by connective tissue, and only surrounded by it. The gland has usually a number of acini connected in a tiny lobule. A minor salivary gland may have a common excretory duct with another gland or may have its own excretory duct. Their secretion is mainly mucous in nature and has many functions such as coating the oral cavity with saliva. The minor salivary glands are innervated by the facial nerve. The minor salivary glands can be traumatized, resulting in enlargement and is commonly called a mucocele.

1.6 TONGUE

The tongue is divided developmentally and anatomically into an anterior two thirds and a posterior one third, separated by the sulcus terminalis, a V-shaped groove with the foramen cecum at the apex (Fig. 1.4). The latter is the site of outgrowth of the thyroglossal duct and in front of the sulcus is a row of vallate papillae (Abd-El-Malek, 1955). Filiform papillae and red, flat-topped fungiform papillae can be seen on the more anterior parts of the tongue.

Two broad sets of muscles move the tongue, namely the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. The extrinsic muscles comprise hyoglossus, genioglossus, styloglossus, and palatoglossus.

The innervation of the components of the tongue is complex and reflects its aforementioned embryological origins (Boyd, 1937). All intrinsic muscles as well as the three of the four extrinsic muscles (the exception being palatoglossus) are supplied by the hypoglossal nerve and are assessed in a cranial nerve examination.

The anterior two thirds of the tongue mucosa are supplied by the lingual nerve (from the mandibular branch of the trigeminal cranial nerve, Figs. 1.4 and 1.5) and the posterior third is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve. Taste for the anterior two thirds of the tongue is provided by the chorda tympani branch of the facial cranial nerve (carried to the tongue by the lingual nerve) and the posterior one third by the glossopharyngeal nerve.

|

A small part of the tongue near the epiglottis receives both its sensory and taste innervation from the internal laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve.

The tongue receives its blood supply primarily from the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery and lingual veins that drain into the internal jugular vein (Moore, et al., 2009). Since the anterior part of the tongue develops from a pair of lingual swellings, the nerves, blood vessels (and to a lesser degree the lymphatics) of each side of the tongue do not cross the midline. This means that the midline of the tongue is a relatively avascular plane enabling dissection along it. It also means that carcinoma developing from one side of the tongue will generally only metastasize to one side, although some crossover does occur near the tip. Damage to the motor supply (Chapter 22) will result in the tongue deviating to the affected side when protruded owing to the action of genioglossus on the unaffected side.

1.7 MUSCLES OF MASTICATION

The four muscles described above are instrumental to the action of mastication and are supplied by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal cranial nerve (Auyong and Le, 2011). Their origins, insertions and actions are demonstrated in Table 1.2 and their attachments to the mandible are demonstrated in Figure 1.6

1.8 PALATE

The palate consists of two parts with differing structure and functions (Fig. 1.7). The hard palate separates the anterior part of the mouth from the nasal cavities, and the soft palate separates the posterior part of the mouth from the nasopharynx superior to it. The hard palate is covered by a mucous membrane and is formed by the palatine processes of the maxillae and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones.

Three foramina open on the oral aspect of the hard palate: the incisive fossa and the greater and lesser palatine foramina. The incisive fossa is a slight depression posterior to the central incisor teeth that carries the nasopalatine nerve as it passes from the nose. Medial to the upper third molar tooth, the greater palatine foramen pierces the lateral border of the bony palate. The greater palatine vessels and nerve emerge from this foramen and run anteriorly on the palate. The lesser palatine foramina transmit the lesser palatine nerves and vessels to the soft palate and adjacent structures.

The soft palate is the movable third of the palate, which is suspended from the posterior border of the hard palate. The soft palate extends posteroinferiorly as a curved free margin from which hangs a conical process, the uvula.

The soft palate is strengthened by the palatine aponeurosis, formed by the expanded tendon of the tensor veli palatini. The aponeurosis, attached to the posterior margin of the hard palate, is thick anteriorly and thin posteriorly. The anterior part of the soft palate is formed mainly by the palatine aponeurosis, whereas its posterior part is muscular.

When a person swallows, the soft palate is initially tensed to allow the tongue to press against it, squeezing the bolus of food to the back of the oral cavity proper (Faiz, Blackburn and Moffat, 2011). The soft palate is then elevated posteriorly and superiorly against the wall of the pharynx, thereby preventing passage of food into the nasal cavity. Laterally, the soft palate is continuous with the wall of the pharynx and is joined to the tongue and pharynx by the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches, respectively.

1.9 PALATINE TONSILS

The palatine tonsils are a pair of dense compact bodies of lymphoid tissue that are located in the lateral wall of the oropharynx (Fig. 1.5). Each tonsil lies in a tonsillar fossa, bounded by the palatoglossus muscle anteriorly and the palatopharyngeus and superior constrictor muscles posteriorly and laterally (Nave, Gebert and Pabst, 2001). In conjunction with tonsillar tissue on the posterolateral tongue and the adenoids within the nasopharynx, it forms the ring of lymphoid tissue found in the pharynx named Waldeyer's ring (Drake, Vogl and Mitchell, 2009). This lymphoid tissue in this ring provides defense against pathogens primarily through the production of immunoglobulin and the development of both B cells and T cells.

REFERENCES

- Abd-El-Malek, S., 1955. The part played by the tongue in mastication and deglutition. Journal of Anatomy, 89, p. 250.

- Auyong, T.G., Le, A., 2011. Dentoalveolar nerve injury. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics of North America, 23(3), pp. 395–400.

- Boyd, J.D., 1937. Proprioceptive innervation of mammalian tongue. Journal of Anatomy, 72, p. 147.

- Drake, R.L., Vogl, A.W., Mitchell, A.W.M., 2009. Gray's anatomy for students. 2nd ed. Elsevier. London:

- du Toit, D.F., Nortjé, C., 2004. Salivary glands: applied anatomy and clinical correlates. Journal of the South African Dental Association, 59(2), pp. 65–6, 69–71, 73–4.

- Ellis, H., Mahadevan, V., 2010. Clinical anatomy: applied anatomy for students and junior doctors. 12th ed. Wiley-Blackwell. London:

- Faiz, O., Blackburn, S., Moffat, D., 2011. Anatomy at a glance. 3rd revised ed. Wiley-Blackwell. Chichester:

- Koussoulakou, D.S., Margaritis, L.H., Koussoulakos, S.L., 2009. A curriculum vitae of teeth: evolution, generation, regeneration. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 5(3), pp.226–43.

- Moore, K.L., Dalley, A.F., Agur, A.M.R., 2009. Clinically oriented anatomy. 6th ed. Williams & Wilkins. Lippincott:

- Nave, H., Gebert, A., Pabst, R., 2001. Morphology and immunology of the human palatine tonsil. Anatomy and Embryology (Berlin), 204(5), pp. 367–73.

- Zhang, L., Xu, H., Cai, Z.G., et al., 2010. Clinical and anatomic study on the ducts of the submandibular and sublingual glands. Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery, 68(3), pp. 606–10.