HISTORY

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations have been used to diagnose superficial fungal infections, known as dermatophytoses, for more than a hundred years. This bedside test has stood the test of time because it provides a rapid and accurate diagnosis in clinical settings where the diagnosis is in doubt. The precise origin of the KOH examination remains unclear.1 However, some of the earliest accounts describe the use of “potash” to help visualize Trichophyton tonsurans in the late 19th century.2,3 Raymond Sabouraud is credited for publicizing the utility of KOH in microscopic examination of dermatophytes in his 1894 piece Le Trichophyties Humaines.1,4 His careful description of technique solidified the importance of KOH in eliciting dermatophytic diagnoses.

By the 20th century, the benefit of the KOH examination was firmly established. Physicians began experimenting with variations of technique and specimen preparation. The KOH preparation was taught to generations of medical students in the fashion of an apprenticeship. Certain mid-century innovations to the KOH examination are still commonly employed today, such as the addition of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to KOH solution. This variation clears keratin more quickly than KOH at room temperature that requires 10–30 minutes or more before the sample can most effectively be examined.5 The KOH examination continues to be taught in clinical settings with physicians passing along their own personal nuances to specimen collection and preparation. The sensitivity of KOH preparation has been reported to be as high as 87–91% highlighting KOH as a necessary diagnostic tool that should be mastered by all physicians treating dermatological problems.6

WHEN TO UTILIZE POTASSIUM HYDROXIDE

Potassium hydroxide preparation is an essential tool for the diagnosis of superficial fungal infections. This test is cost-effective and has a high sensitivity when performed by an experienced individual. However, to save time or because they have not developed this skill, some practitioners do not perform KOH preparations preferring empiric antifungal therapy. Unfortunately, this causes a delay in diagnosis and the majority of papulosquamous conditions that are clinically similar to tinea will not respond to antifungal creams.7 Other clinicians eschew KOH preparation in favor of using a combination of a corticosteroid/azole antifungal agent. The anti-inflammatory effect of topical steroids, however, decreases the effectiveness of the antifungal cream component and most patients with tinea will not clear.

Superficial dermatophyte infections are classified by their location on the body because of tinea's distinctive clinical features at each site. Examples include tinea pedis which often presents subtly as scaling and maceration between the toes, and tinea cruris, also known as ‘jock itch’, which presents as erythematous moist and/or scaly patches involving the medial thighs and may spread to involve the pubic area and lower medial buttocks.4

Fig. 1: Tinea corporis: Large patches of subtle scaling most marked at the periphery. This is a very common appearance of tinea corporis.

Fig. 2: Tinea corporis. This 4 cm patch of scaling shows more marked scaling at the periphery than noted in Figure 1.

Fig. 3: Onychomycosis. The great toe, third and fourth tonails show distal subungual onychomycosis with yellowing and thickening of the toenails and lifting of the distal nail (onycholysis). The second toe shows white friable changes typical of superficial white onychomycosis.

Fig. 4: Tinea faciei. An erythematous patch with slight scaling is present on the cheek of an elderly man. The classic scaly advancing margin of superficial fungal infections is not present in this case. A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation showed septate hyphae confirming the correct diagnosis.

Tinea corporis has a similar scaling annular appearance but presents on the trunk or extremities (Figs. 1 and 2), while tinea faciei involves the face. Tinea capitis may show little erythema and only scaly patches of alopecia but can less commonly present with boggy inflammatory papulopustules or nodules on the scalp. Onychomycosis, or tinea unguium, is a fungal infection of the nails, which may present as distal thickening and dystrophic changes (distal subungual onychomycosis) or opaque, friable, whitish superficial spots on the nail plate (superficial white onychomycosis) (Fig. 3). In some cases, an erythematous minimally scaly patch may show no accentuation at the periphery. This is why a KOH preparation should be considered in any scaly patch (Fig. 4).

Many other cutaneous disorders show similar clinical morphology. Psoriasis, various forms of eczema, and pityriasis rosea should be included in the differential diagnosis and can quickly be ruled out by a positive KOH, thus negating the need for a biopsy in many cases. Other entities that can be mistaken for superficial fungal infections include erythema annulare centrifugum, lichen planus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and parapsoriasis.85

Fig. 5: Pityriasis versicolor. Superficial scaly, mildly erythematous patches are present on the trunk.

Fig. 6: Pityriasis versicolor. Extensive tan, confluent patches with fine scaling are present on the trunk.

Yeast organisms, such as Malassezia furfur and Candida albicans, also can cause superficial fungal infections. M. furfur is the etiologic agent of “tinea” versicolor (pityriasis versicolor). It presents with tan hyperpigmented and/or hypopigmented macules and patches with overlying scale that is most often found on the trunk and proximal extremities (Figs. 5 and 6). Some patients have associated pruritus. Due to its variable appearance, it can be mistaken for pityriasis alba or occasionally vitiligo. Candida albicans is responsible for a myriad of clinical infections, including thrush, perleche/angular cheilitis, intertriginous dermatitis, vulvovaginitis, and balanitis. It is imperative to perform a KOH examination on any rash suspicious for superficial fungal infection to ensure a prompt and accurate diagnosis, thus avoiding unnecessary delays and proper therapy.

MATERIALS NEEDED

Materials required include:

- Microscope slide and cover slip

- Number 15 scalpel blade

- A 10–20% KOH solution combined with contrast dye of choice (KOH with DMSO [Dimethyl Sulfoxide] optional)

- Methanol burner or match/lighter (optional)

- Microscope

OBTAINING AN ADEQUATE SAMPLE

Where

It is best to obtain sample material from specific areas of rash to ensure the highest diagnostic yield. In suspected dermatophytic infections, procuring scale from the active outer border of the lesion is more likely to garner a positive result compared with material obtained from the center of the lesion.8,9 For cases of possible Malassezia, sampling the characteristic diffuse scale of the patches is appropriate. In suspected superficial candidal infections it is best to obtain specimen from the moist, macerated, caseous matter.

For nail sampling, one should target the white or yellow, crumbly areas, as these regions are most likely to consist of active infection.10 If no single apparent area is present, sampling from the distal subungual debris is appropriate with an attempt to get material from the most proximal area of involvement preferred. If concerned about paronychia, a candidal skin infection affecting the periungual skin, obtain pus from underneath the nail fold for microscopic examination, either by compression or incision with a number 11 scalpel blade of the inflamed tissue.

When considering tinea capitis, obtain scale scrapings from the base of the broken hair and the affected scalp. Trichophyton tonsurans is the most common cause of tinea capitis in children and is referred to as the “black dot ringworm” with short dark broken hairs giving the appearance of black dots.6

Fig. 7: Proper scraping technique. The advancing margin of this scaling patch was selected to obtain a sample. The skin is gently scraped with a number 15 scalpel blade. The sharp edge of the blade trails behind to avoid lacerating the skin.

Fig. 8: Proper scraping technique. A large amount of scale is collected to increase the sensitivity of the potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation.

It is important to sample and examine these hairs for endothrix spores. Specimen can be easily obtained with gentle scraping as outlined below. Occasionally, only scaly patches mimicking seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis of the scalp may be seen.

How

After a suitable area has been selected, clean the area gently with an alcohol pad. The moisture from the pad will facilitate scale collection by causing the scale to stick more readily to the scraping device.7 Alternatively, a dampened gauze can be used to moisten the dry scale to help with specimen collection. A number 15 blade is most commonly used to obtain scale. Hold the slide perpendicular to the skin of the affected area and begin scraping with the sharp end of the blade “trailing behind”, so as not to lacerate the skin (Fig. 7). When collecting samples for KOH preparation it is important to remember two key facts. First, and very importantly, a large amount of scale must be collected in order to maximize the chance of visualizing any superficial fungus that may be present (Fig. 8).11,12 Second, each microscopic slide should be immediately covered with a cover slip to ensure that collected specimen is not lost (blown off by the air) while transferring the slide from the examination room to the microscope. In patients who will not remain still, a microscope slide, a curette, or even a toothbrush have been used in place of the sharp blade.9

PREPARATION METHODS

Staining/Ink

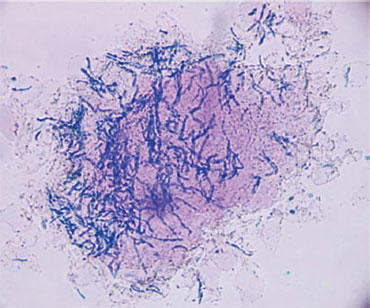

In order to accurately view the specimen a clearing agent must be added to digest the keratin. KOH serves as the most commonly used agent.7,8,13 However the standard KOH preparation lacks color contrast. This deficit may make it difficult for individuals to differentiate between keratinocytes (walls) and fungal elements. The addition of contrast dyes that stain the fungal spores and hyphae facilitate visualization and increase sensitivity (Figs. 9 and 10). A number of KOH solutions with contrast dyes are commercially available. Studies of these solutions demonstrate varying sensitivities (Table 1).14,15 Our experience with any of the contrast dyes shows much higher sensitivity than reported with Parker Super Quink® ink (Helms, Brodell).16,17

Applying the clearing solution is best performed as follows: draw up KOH/ink solution in an eye dropper and place one to two drops on each side of the cover slip allowing the solution to diffuse through capillary action beneath the slide (Figs. 11A and B).97

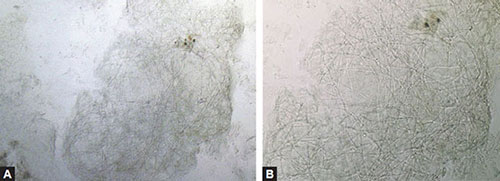

Figs. 9A and B: (A) Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation without stain. A preparation using KOH with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) demonstrates hyphae that blend in with the walls of background keratinocytes (100X). (B) KOH preparation closer view of hyphae demonstrates similarity of hyphae and cell walls (400X).

Figs. 10A and B: (A) Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation with stain. Chicago blue stains hyphal walls blue to differentiate them from cell walls (100X). (B) KOH preparation with stain. Blue hyphae are easily seen on higher power when compared to unstained keratinocyte walls (400X).

|

To further facilitate diffusion, press lightly on the cover slip and employ a side-to-side technique to flatten out the layer of scale and to mobilize excess solution to the edge7 (Fig. 12A). In scrapings from patients with tinea capitis, care must be taken to avoid exerting too much pressure on the slide as this can express the spores from within the hair shaft altering the “typical picture” seen with the spores neatly in line inside the hair shaft.8 Excess solution can be gently blotted away with a paper towel, lens paper or tissue7,9 (Figs. 12B and C).8

Figs. 11A and B: (A) Application of potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution to slide. KOH solution is applied at the edge of the cover slip. (B) Application of KOH solution to slide. Capillary action moves the KOH solution underneath the cover slip.

Figs. 12A to C: Removing excess potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution. (A) Inked KOH is evenly distributed under the entire cover slip. (B) A paper towel is folded over the slide and pressed gently to remove excess liquid and flatten clumps of cells. (C) The towel is unfolded and the slide is ready for viewing under the microscope.

Heat/Time

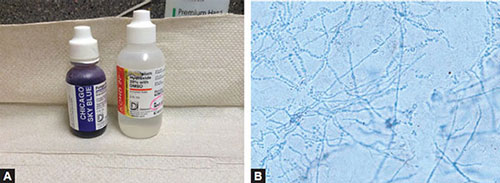

Prior to microscopic visualization, the utilization of a heat source is often used to accelerate keratinocyte digestion when using KOH. A methanol burner can be used, but care must be taken to not heat the specimen to boiling as this can promote KOH crystallization and cause artifact.8 Sampling from the hair and nails may require more heating to digest the thicker keratinous material. Another chemical that may be used to clear keratin is DMSO which eliminates the need for heating KOH solution to quickly clear keratin.18 Commercial preparations are available that contain KOH and DMSO, and one contains KOH, DMSO, with a dye (Chlorazol Black E™). Although it is common to immediately examine the slide after heating when using KOH alone, waiting 5–15 minutes or longer before viewing is most ideal to allow adequate keratinocyte digestion and maximize sensitivity. Finally, KOH with DMSO can be mixed with Chicago Sky Blue™ by adding one drop of each to the slide which will aid in rapid clearing without heating and at the same time allow inked hyphae to be more easily identified (Figs. 13A and B).9

Figs. 13A and B: (A) Bottles showing Chicago sky blue stain 1% with 8% KOH and a bottle of KOH 20% containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The Chicago sky blue stain is very dark when used alone. Chicago sky blue (CSB) stain can be added to the routine potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet-mount to provide a color contrast and facilitate the diagnosis of dermatomycoses. (B) Potassium hydroxide (KOH) option favored by authors. One drop of Chicago blue KOH may be dropped onto the slide with one drop of a commercially available KOH 20% with DMSO to make a solution with a lighter background coloration. The use of the DMSO also leads to more clearing of keratin.

INTERPRETATION AND MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

To best visualize a KOH preparation, adjust the microscope, so that the condenser is as far down as possible and adjust to a lower intensity of lighting. Limiting the light better emphasizes the contrast between keratinocytes and the fungal spores and hyphae.8 It is important to be comfortable in recognizing the microscopic features of characteristic fungal elements (Table 2). You likely will have to increase the amount of light as you move to higher powers to confirm what appear to be fungal elements.

Hyphae and spores can also be seen in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained biopsy specimens. However, they are much more easily identified when periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-diastase staining is used (Fig. 14). This also demonstrates why scraping of superficial fungal infections show fungal elements.

Benefits to Alternative Therapies

Potassium hydroxide is a rapid, cost-effective technique for diagnosing superficial fungal infections. The sensitivity of KOH is dependent on the examiner's skill and expertise.7,19 It has been reported that obtaining a positive laboratory test prior to initiating antifungal therapy is more cost-effective than beginning empiric antifungal therapy without a confirmatory diagnosis.18 As a multitude of clinical entities can present similarly to superficial fungal infections, utilizing empiric antifungal therapy in place of laboratory testing can delay diagnosis and increase overall costs.10

Fig. 14: Skin biopsy demonstrating hyphal elements in stratum corneum with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain.

Fig. 15: Hyphal elements and spores typical of tinea versicolor stained with KOH and Parker Super Quink ink (400X).Courtesy: Adam Byrd, MD

Periodic acid-Schiff staining of a biopsy specimen has the highest sensitivity of superficial fungal diagnostic tests (Fig. 14).6 However its high cost makes it a less attractive test when compared to KOH preparation. KOH is also as a screening test to fungal culture because of its increase sensitivity.19 In addition, fungal culture is much more time intensive and expensive when compared to the rapid in-office results of KOH.19 It is particularly important to perform a KOH when tinea versicolor is suspected. This yeast cannot be cultured on regular fungal media but has a characteristic picture under the microscope often referred to as “spaghetti and meatballs” with short hyphal elements and many small round spores (Fig. 15).

Combining KOH with calcofluor-white, a fluorescent dye, has been described as a sensitive method for evaluating potential superficial infections. However, there are disadvantages to this process since it requires the use of a fluorescence microscope. In addition, it has been shown to have a higher false-negative rate when compared to KOH preparation with ink.6

The benefits of utilizing KOH preparation to diagnose superficial infections are, therefore, multifactorial. The test is highly sensitive at detecting infection, timely and cost-effective, and relatively easily mastered without an extensive amount of training.

Limitations

The primary limitation of KOH preparation is its dependence on operator's expertise. There is a positive correlation between examiner's skill and the sensitivity of KOH preparation with or without stains or ink.7 Examiners unfamiliar with microscopic interpretation and the steps that produce an adequate KOH preparation may misinterpret the test as a false-negative or false-positive result. Multiple tips and tricks described in this chapter should help alleviate operator-dependent errors.

Causes of false-negative results may also include previous treatment with antifungals and the collection of inadequate samples. Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion for superficial fungal infection in the presence of a negative KOH test should prompt repetition of KOH and possibly a fungal culture. Only on a rare occasion should empiric therapy be indicated, if the clinical picture is so clearly suggestive of fungal infection.8

False-positive results, although less common, can occur. These are typically attributed to observation error by the examiner. Intercellular spaces, especially with overlapping cell walls, and artifacts, such as hair, clothing fibers, lipids, or KOH 11crystals caused by overheating can all be misinterpreted as hyphae or spores. These errors tend to be alleviated with experience.

REFERENCES

- Dasgupta T, Sahu J. Origins of the KOH technique. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(2):238–41.

- Fox T. On ringworm of the head, and its management. Lancet. 1877;110:719–22.

- Thin G. Contributions to the pathology of parasitic diseases of the skin. Br Med J. 1982;2(1129):301–5.

- Sabouraud R. Les Trichophyties Humaines. Paris, France: Rueff & Cie; 1894.

- Zaias N, Taplin D. Improved preparation for the diagnosis of mycologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93(5):608–9.

- Lily KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):620–6.

- Wilkison BD, Sperling LC, Spillane AP, et al. How to teach the potassium hydroxide preparation: a disappearing clinical art form. Cutis. 2015;96(2):109–12.

- Brodell RT, Helms SH, Snelson ME. Office dermatologic testing: the KOH preparation. Am Fam Physician. 1991;43(6):2061–5.

- Bronfenbrener R. Stains and smears: resident guide to bedside diagnostic testing. Cutis. 2014;94(6):E29–30.

- Shelley WB, Wood MG. The white spot target for microscopic examination of nails for fungi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6(1):92–6.

- Merrill N, Mallory SB. Superficial fungal infections in children. J Ark Med Soc. 1987;84(6):235–8.

- McBurney EI. Diagnostic dermatologic methods. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1983;30(3):419–34.

- Swartz JH, Lamkins BE. A rapid, simple stain for fungi in skin, nail scrapings, and hairs. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:89–94.

- Tambosis E, Lim C. A comparison of the contrast stains, Chicago blue, chlorazole black, and Parker ink, for the rapid diagnosis of skin and nail infections. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(8):935–8.

- Sigma-Aldrich. (2017). Safety Data Sheets Version 4.1. [online] Available from www.sigmaaldrich.com/united-kingdom/technical-services/material-safety-data.html. [Accessed March, 2017].

- Levitt JO, Levitt BH, Akhavan A, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture relative to clinical assessment in the evaluation of tinea pedis: a pooled analysis. Dermatology Research Practice. Volume 2010(2010), Article ID 764843, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2010/764843.

- Prakash R, Prashanth HV, Ragunatha S, et al. Comparative study of efficacy, rapidity of detection, and cost-effectiveness of potassium hydroxide, calcofluor white, and Chicago sky blue stains in the diagnosis of dermatophytoses. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55(4):e172–5.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrew's Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, 11th edition. New York, NY, USA: Elsevier-Saunders; 2011.

- Mehregan DR, Gee SL. The cost effectiveness of testing for onychomycosis versus empiric treatment of onychodystrophies with oral antifungal agents. Cutis. 1999;64(6):407–10.